Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Pop quiz:

What do Saint Walpurgis Night (the German holiday), the Night of Witches (the Czech holiday), Calan Mai (the Welsh holiday), and the European festival of May Day all have in common—apart from taking place at the end of April/beginning of May?

Turns out they all might be rooted in the same ancient Celtic festival: Beltane.

Yes, the reason why people make merry around giant wooden poles every May first, with the flowers and the garlands and the hallucinogenic tea—wait, sorry, that last part’s from the movie Midsommar, my bad—is because…

Well, I mean, it’s a fertility festival, isn’t it?

The phallic symbolism of the Maypole, at first glance, seems obvious.

However, there is a school of thought that says if Maypoles were meant to represent phalluses then historically people would’ve carved them to look more like phalluses, which there’s no evidence of.

So maybe the Maypole’s symbolism isn’t rooted in fertility, but mythology.

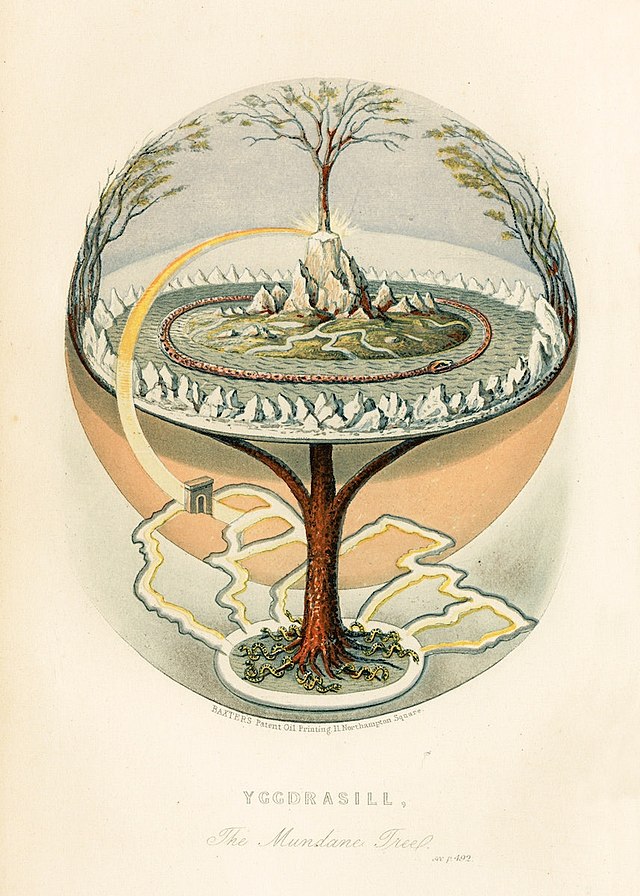

Indeed some scholars argue that the Maypole is a representation of the axis mundi, or world axis—a cosmic pillar connecting the different planes of existence.

And more specifically, given that ancient Germanic peoples—like ancient Celtic peoples—considered certain trees to be sacred, it’s possible the Maypole represents a specific iteration of the axis mundi known as the world tree, with its roots reaching down into the underworld and its branches spreading out into the different realms.

And here’s where the theory of a Celtic origin for the Maypole—and May Day—really starts to take root. (I’m sorry.)

To clarify, this isn’t my theory—it belonged to J. A. MacCulloch, one of Scotland’s most famed Celtic scholars.

MacCulloch equated the lighting of bonfires on hillsides, one of the “chief ritual acts at Beltane,” with the kindling of German need-fires, which was a superstitious practice employed by shepherds to protect livestock from disease. The shepherds would use branches to create friction fires and then drive their livestock between them.

Incidentally, in one of the earliest written accounts of a Beltane celebration, courtesy of the Irish bishop and king of Munster, Cormac mac Cuilennáin, who died in 908 CE, Irish pagans are depicted driving cattle between two druid-lit bonfires to inoculate them against disease.

It certainly seems like the German tradition and Irish tradition are one in the same.

But MacCulloch takes this a step further, speculating that the fires used to perform these Beltane (or proto-Beltane) livestock purification rituals were originally lit beneath sacred trees.

Or the pagans would chop down trees and stick them in the centers of the bonfires.

Or perhaps wood poles would be decorated with greenery and surrounded with fuel before being ceremoniously ignited.

See where he’s going with this?

To quote MacCulloch:

“These trees survive in the Maypole of later custom, and they represented the vegetation-spirit, to whom also the worshippers assimilated themselves by dressing in leaves. They danced sunwise round the fire or ran through the fields with blazing branches or wisps of straw, imitating the course of the sun, and thus benefiting the fields. For the same reason the tree itself was probably borne through the fields. Houses were decked with boughs and thus protected by the spirit of vegetation.”

source: The Religion of the Ancient Celts

Of course, it’s easy to discern a blueprint for May Day in MacCulloch’s description of Beltane. The pole. The greenery. The dancing in circles. The hallucinogenic—wait, sorry, almost did it again.

But look at me, getting ahead of myself here, like a bull charging between two stacks of yet-to-be-lit firewood.

In order to properly investigate MacCulloch’s theory, we first need to understand the basics of Beltane and shine a light on why the ancient Celts celebrated it.

What Is Beltane?

Beltane is an ancient Celtic festival that marks the beginning of summer and the transhumance or seasonal migration of livestock from winter lowlands to summer pastures.

To quote historian Thomas Cahill, the springtime celebration was “distinguished by bonfires, maypoles, and sexual license” (source: How the Irish Saved Civilization).

Traditionally celebrated on the evening of April 30th and into the early morning of May 1st, Beltane is a cross-quarter day, meaning it falls roughly halfway between an equinox and a solstice (in this case, the spring equinox and the summer solstice).

Less commonly known as Cétshamhain, meaning “first of summer,” the name Beltane is derived from the Old Irish for “lucky fire” or the “the two fires,” according to the glossary of the aforementioned Cormac mac Cuilennáin.

Flash forward about a thousand years and historian Peter Berresford Ellis asserts in his A Dictionary of Irish Mythology that Beltane actually means the “fires of Bel.”

The Bel in question here is thought to be the Celtic god of life/healing—and possible sun god—Belenus. More about him in a bit.

Another camp posits that the festival owes its name to a Lithuanian goddess of death, Giltinė, while another camp—this one led by Scottish antiquarian James Napier—argues that Beltane means not Bel’s fire, but “Baal’s fire,” and is a reference to a Phoenician god.

To quote from Napier’s book Folk Lore: Superstitious Beliefs in the West of Scotland:

“Baal (Lord) was the name under which the Phoenicians recognized their primary male god, the Sun: fire was his earthly symbol and the medium through which sacrifices to him were offered.”

Can you imagine that? A Phoenician origin for the Celtic festival of Beltane?

Scottish anthropologist and folklorist Sir James George Frazer, for one, could not. To quote from Frazer’s masterwork of comparative mythology, The Golden Bough:

“The etymology of the word Beltane is uncertain; the popular derivation of the first part from the Phoenician Baal is absurd.”

In Frazer’s estimation, Beltane has a more secular etymology, one devoid of a divine namesake. And I quote:

“Bal-tein signifies the fire of Baal. Baal or Ball is the only word in Gaelic for a globe. This festival was probably in honour of the sun, whose return, in his apparent annual course, they celebrated, on account of his having such a visible influence, by his genial warmth, on the productions of the earth.”

Now there is yet another camp of scholars who argue that Beltane is derived from an old Celtic word “belo-teniâ” meaning “bright fire,” but the underlying implication is the same as with Frazer’s interpretation:

Beltane isn’t a devotional celebration for a particular god, it’s a celebration of light.

Or…maybe it’s both?

Who Is the Celtic God Belenus? (And Did He Really Inspire Beltane?)

One of the oldest references to the Celtic god Belenus comes from Julius Caesar (yes, that Julius Caesar), writing in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (The Gallic Wars).

Granted, Caesar didn’t reference Belenus by his native name.

Being the arrogant Roman that he was, he noted that the Gaulish Celts worshiped “Apollo”—whom Caesar considered to be the closest Greco-Roman equivalent.

Apollo is the god of light and the Sun, and healing and diseases, and a bunch of other things, but I have to admit, he does line up pretty nicely with Belenus, who many sources consider to be a solar god and a god of healing.

What’s more, the name Belenus likely means “bright one” or the “shining one,” although that’s still up for debate.

Some scholars argue Belenus originally meant something like “master of power,” which…if anything else, is an awesome superhero name.

A cognate of Belenus appears in Irish mythology (specifically as recorded in the Lebor Gabála Érenn) as Bilé.

Known as the life-giver, Bilé is not a solar deity, but the god of life and death who comes from the land of the dead.

Bilé is occasionally referred to as “Father of Gods and Men” and made husband to the Irish mother goddess Danu a.k.a. Dana a.k.a. Anu, namesake of the Tuatha De Danann.

Actually, now I see more of a parallel between Bilé/Belenus and the aforementioned Lithuanian goddess of death, Giltinė.

Both are deities associated with mortality (which may or may not be coincidental).

And when you consider that the Encyclopaedia Britannica makes it very clear that Belenus was not a sun god, noting that there was “no Celtic evidence for the worship of the sun as such,” it kind of shakes that foundation of thinking that Beltane and the fires were all about worshiping a solar deity.

Regardless of what Belenus represented, his cult was a large and powerful one, stretching from Italy to Ireland.

As a result, many European place names bear his stamp. In London, for example, there’s Billingsgate, a derivation of Belinos’ Gate.

In the municipality of Aquileia in Italy there’s the village Beligna.

There’s also the Beltany stone circle in County Donegal, Ireland, which may have a connection to either the festival of Beltane, the Celtic god Bel, or both.

What’s more, according to Ellis, many notable Celtic kings of Britain took the name Cunobelinus, or “Cunobel” in Brittonic (meaning “Hound of Bel”), including the High King of Britain the Romans encountered in 5 BCE.

This king would go on to serve as the inspiration for William Shakespeare’s character Cymbeline.

All this to say, it tracks that the Celts would’ve named one of their most important festivals after this god—Belenus was clearly a significant figure in the ancient Celtic world, even if he had nothing whatsoever to do with the sun.

The Christianization of Beltane

Assuming that Beltane or rather some unattested continental, Proto-Celtic progenitor of the festival, really was the original May Day that inspired similar celebrations across Europe, one has to wonder:

Why did Beltane disappear?

The answer, of course, is that it didn’t.

And no I’m not just talking about the Neopagans and Neodruids and Wiccans who rediscovered Beltane, but also Christians who unknowingly perpetuated and continue to perpetuate Beltane customs.

Remember Walpurgis Night, which I mentioned up top, which is also celebrated on May Eve?

Yeah, turns out for centuries folks have celebrated this Christian festival by making merry around evening bonfires.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Walpurgis Night is derived from the “merging of the ancient pagan celebration of Beltane with the commemoration of the canonization of the Christian Saint Walpurga (l. c. 710 – c. 777 CE).”

FYI: Walpurga was a British-born Christian missionary and healer known for her ability to combat witchcraft.

Hence, the fires are supposed to represent, uh…burning witches, I guess?

Look, the Czech version is literally called “Burning of the witches,” Pálení čarodějnic, and they don’t just light bonfires but burn giant witch effigies in said bonfires.

But there’s more to this fiery custom than showing disdain for witches while simultaneously showing veneration for Saint Walpurga.

To quote historian Javier A. Galván’s book, They Do What? A Cultural Encyclopedia of Extraordinary and Exotic Customs from Around the World:

“Early Christians in this region believed that, during Walpurgis Night, evil powers were at their strongest, and people had to protect themselves and their livestock by lighting fires on hillsides.”

You catch that part about the livestock?

If there was any doubt before, it certainly seems clear now that the ostensibly Christian Walpurgis Night and its regional variants actually began as Beltane-like transhumance festivals.

The only issue, of course, is that there is no record of ancient Celts having celebrated Beltane-like transhumance festivals in (or near) those traditionally Germanic regions.

Now, it’s possible the Gauls or another continental Celtic tribe celebrated an unattested version of Beltane and then passed that tradition onto the ancient Germanic tribes, but I propose a much simpler explanation.

Beltane and May Day: A Common Origin

Celtic peoples, Germanic peoples—at the end of the day, they all stem from the same people: Proto-Indo-Europeans, a loose network of tribes that originated in the steppes of what is now Ukraine and southern Russia.

The study of animal bones confirms that prehistoric Eurpoeans moved livestock seasonally. So it’s easy to imagine that for hundreds or even thousands of years before Celtic peoples and Germanic peoples branched off as distinct groups, there was a shared calendar based around pastoralism.

Hence, the end of April/beginning of May had been an important time well before the festivals of May Day or Beltane were formalized.

Back then, life itself hinged on transhumance migrations going smoothly and livestock staying healthy.

As a result, rituals and superstitions emerged to encourage that smooth transition between the pastoral seasons.

Of course, if this proto-Beltane/May Day really was celebrated amongst the Proto-Indo-Europeans, we’d expect to find variants not only amongst the Celtic and Germanic tribes, but amongst other European tribes as well.

And we do.

Most notably, the Romans, who celebrated Floralia between April 28th and May 3rd.

The festival, which featured lots of drinking and pleasure-seeking and flower-wearing and gladiatorial games and the releasing of goats and hares and, in one instance, a tightrope-walking elephant (no, seriously), was held in honor of Flora, Roman goddess of fertility, flowers, and vegetation.

Animal sacrifices were made to the goddess during her namesake festival as well.

Now, here’s where the story gets really interesting, because after the Roman and Celtic and Germanic versions of the Proto-Indo-European May festival evolved, each taking on its own distinct characteristics, they reconverged.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Beltane “merged” with Germanic May Day.

And to quote Jennifer Cutting, Folklife Specialist at the U.S. Library of Congress, “the rituals of the Roman floralia were blended into Celtic Beltane rituals as a May festival.”

Thus, the modern May Day, the one that exists in the popular imagination, with the flowers and the dancing and the burning people alive in bear carcasses—sorry, Midsommar again, last time I promise—is really an amalgamation of different traditions that were perhaps all once rooted in a common Proto-Indo-European festival.

As for the origins of the maypole, the jury’s still out.

But of all the explanations I’ve come across, this one’s my favorite:

People started putting up maypoles because…it was fun. And convenient for decorating.

That’s why you see similar structures being used for ritual purposes in ancient India and Northern Africa, as well as in some pre-Columbian Latin American cultures.

It wasn’t Ancient Aliens—it was, essentially, prehistoric party planners from different cultures arriving at the same idea independently. That idea being:

Wouldn’t it be neat if we took a big log and stuck it upright in the center of the village during our next big bash?

To elaborate on this theory in more respectable terms, I’ll leave you with the following excerpt from historian Ronald Hutton’s book The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual year in Britain, in which the author summarizes Swedish folklore scholar C. W. von Sydow’s understanding of the maypole’s symbolism—or lack thereof.

And I quote:

[T]he poles, like the fetching of green branches, were simply signs that the happy season of warmth and comfort had returned. They were useful frameworks upon which garlands and other decorations could be hung, to form a focal point for celebration.”

P.S. Want to learn more about ancient Celtic festivals and spirituality? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over… Learn more…

Irish Myths in Your Pocket

40+ images, hundreds of fascinating facts about Irish mythology, and one Celtic Otherworld-shattering showdown between Ireland’s two greatest legendary heroes. That’s just a sampling of what you’ll find crammed into the nooks and crannies of this pocket-sized guide to Irish mythology. And when I say pocket-sized, I mean literally pocket-sized (4 inches by 6 inches). Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

Pyles of Books called Neon Druid “a thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth.” Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic. Learn more…

More the listening type?

I recommend the audiobook The Path of Druidry: Walking the Ancient Green Way by Penny Billington (narrated by Jennifer M. Dixon). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 15-hour audiobook for free.

No constructive thoughts – just that I read Walpurgis Night as Waluigi Night. Good post.

LikeLike

Just added your blog to my RSS feed. I hope to find inspiration in Irish folklore for my writing, keep the posts coming

LikeLike