Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Norse mythology has Mjölnir, the magical, skull-smashing hammer of Thor.

British mythology boasts Excalibur, the sword that granted King Arthur “supreme executive power” after some “watery tart” threw it at him (source: Monty Python).

Greek mythology gets the trident of Poseidon, that famed, three-pronged fork wielded to such great, watery effect by the god of the sea and storms.

But what about Irish mythology?

Rarely do the mythical weapons of Ireland appear in popular culture. But as you’ll soon discover, that’s not because its arsenal is lacking.

Irish mythology, the most well-preserved form of Celtic mythology, is brimming with swords, spears, shields, and other weapons that have served Irish heroes and gods (and monsters) both well and not so well on the battlefield.

Some of these weapons are instilled with magical properties, some are sentient and seem to have lives of their own, and still others earned their legendary status based solely on the power and prowess of their wielders. All have earned their place in one of Western Europe’s most vibrant mythologies.

The following is a comprehensive(ish) list of the most famous weapons of Irish mythology, organized by type.

Pssst. You can watch a video adaptation of this post right here. (Text continues below.)

Swords From Irish Mythology

1. Caladcholg (Hard Dinter)

Also given as Caladbolg (meaning “hard blade” or “hard “cleft”), this was the sword of Fergus mac Roth (a.k.a. mac Róich), former king of Ulster who gave up his throne to Conchobhar mac Nessa. During the Táin bó Cuailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley), the longest story in Irish mythology’s Ulster Cycle, Fergus mac Roth famously uses Caladcholg to level the three bald-topped hills of Meath with three strokes of his blade. While not all mythologists agree, it’s possible that Excalibur (Welsh: Caledfwlch), legendary sword of Britain’s King Arthur, was inspired by stories of Fergus mac Roth’s sword. To quote from Irish writer and translator T. W. Rolleston’s 1911 book Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race:

The sword of Fergus was a fairy weapon called the Caladcholg (hard dinter), a name of which Arthur’s more famous Excalibur is a Latinised corruption.

2. Claíomh Solais (The Sword of Light)

Claíomh Solais (also: Claimh Solais, Cliamh Soluis, and Claidheamh Soluis) was the sword of Nuada of the Silver Hand, the first ruler of the Tuatha Dé Danann who lost his hand (or arm, it’s still up for debate) in the first Battle of Magh Tuireadh. One of the Four Treasures (or Jewels) of the Tuatha Dé Danann, Claimh Solais was sometimes described as Nuadu’s Cainnel (a glowing bright torch). Once unsheathed, no enemy could survive its wrath. To quote from Celtic scholar Whitley Stokes’ 1891 translation of the Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Moytura): “Out of Findias was brought the Sword of Nuada. When it was drawn from its deadly sheath, no one ever escaped from it, and it was irresistible.” Claimh Solais is the first in a long folkloric tradition of glowing swords, which includes Cruaidín Catutchenn (see below).

3. Cruaidín Catutchenn (The Hard-Headed Steeling)

While it’s also known as Socht’s sword, Cruaidín Catutchenn most famously belonged to the Ulster hero Cúchulainn, the Hound of Culann. According to Echtra Cormaic i Tir Tairngiri (Cormac’s Adventure in the Land of Promise), the sword had “a hilt of gold and a belt of silver” and “shone at night like a candle.” Imbued with magical properties, Cruaidín Catutchenn could cut a hair off a man’s head without touching his flesh and more impressively (and disturbingly) could cut a man in half without either half knowing “what had befallen the other.”

In his 1987 A Dictionary of Irish Mythology, historian Peter Berresford Ellis notes that Cruaidín Catutchenn is occasionally confused with Caladcholg (see above) because its name has the same root, crúaid, meaning “hard.” (Cruaidín is the diminutive form.) What’s more, given its glowing nature, some scholars—T. F. O’Rahilly included— interpret Cruaidín Catutchenn as a direct folkloric descendant, if you will, of the aforementioned Claíomh Solais. To quote O’Rahilly: “Cúchulainn possessed…Cruaidín Catutchenn, which shone at night like a torch. In folk tales the lightning-sword has survived as ‘the sword of light’ (an cloidheamh solais), possessed by a giant and won from him by a hero,” (source: Early Irish History and Mythology, 1946).

4. Fragarach (The Answerer)

Fragarach (also: Freagarthach, Frecraid) originally belonged to Manannán mac Lir, Irish sea-god and stepfather to the Irish sun-god, Lugh. Upon Lugh’s departure from Tír na mBeo (the Land of the Living), Manannán gifts him the sword along with other magical items, including a horse—Aonbharr (also: Énbarr)—that can gallop over land and sea alike, and a boat—a currach named Sguaba Tuinne (or “Wave-sweeper”)—that can read a navigator’s thoughts and adjust its course accordingly. So yes, that means the autonomous vehicle is the brainchild of Irish mythology. But I digress…

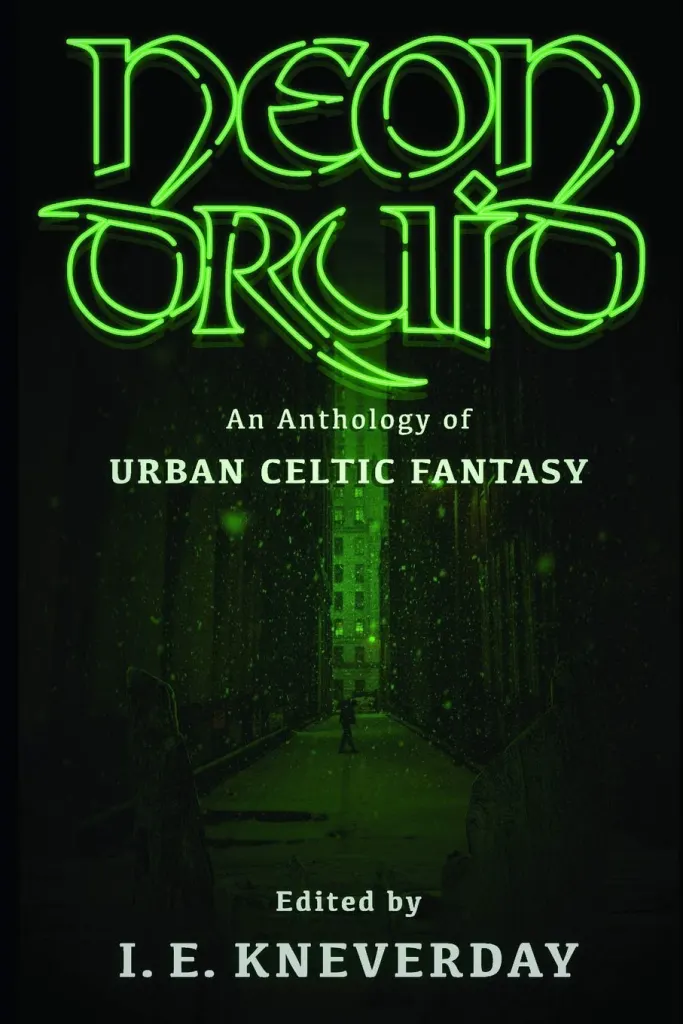

Fragarach was a “terrible sword” that could “could cut through any mail,” according to Rolleston (source: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 1911). Ellis, for his part, adds that “every wound [Fragarach] made was mortal,” (source: A Dictionary of Irish Mythology, 1987). In later legend, Fragarach becomes one of the magical items found within the Treasure Bag of the Fianna, also known as the Crane Bag. (The items inside can only be removed at high tide, otherwise the bag remains empty.). And in later, later legend, the sword features prominently in author R. J. Howell’s modern Celtic fantasy short story “Fragarach,” which is part of my Neon Druid collection.

Disclaimer: If you go on Wikipedia, there is a dubiously sourced entry about Fragarach actually belonging to Nuada of the Silver Hand, who then gifts the sword to Lugh after losing his hand in battle. And while I can’t find any source material to support this claim, it is interesting to note that in Irish poet and Celtic mythologist Ella Young’s 1909 work The Coming of Lugh: A Celtic Wonder-Tale Retold, Manannán gifts Lugh not Fragarach, but the “Sword of Light.” Young even refers to the sword as the “fourth Jewel,” making clear that this is indeed a reference to the, or at least a, Claíomh Solais—a weapon that traditionally belonged to Nuada. As we learned from O’Rahilly in the previous section, the “sword of light” or “lightning-sword” is a recurring motif in Irish folklore. Hence, it’s easy to see how storytellers might mix up the names of these swords (either intentionally or unintentionally) in their interpretations and retellings.

5a. Fraoch Mór (Great Fury)

5b. Fraoch Beag (Little Fury)

In addition to Fragarach (see above), the ocean-god and Otherworld-overseer Manannán mac Lir carried two swords that were both called Fraoch (Fury): Fraoch Mór (Great Fury) and Fraoch Beag (Little Fury)—although it’s likely that Little Fury was actually a dirk, or short dagger. These weapons reappear in later myths, passed down from Manannán mac Lir to the love god Aengus Óg, and from Aengus Óg to his foster-son Diarmuid Ua Duibhne (also: Diarmid O’Dyna).

Diarmuid—nickname: Diarmuid of the Love Spot—was a warrior of the Fianna, best-known for his role in the Fenian Cycle tale Tóruigheacht Dhiarmuda agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne). Long-story short: The dude runs off with the princess Gráinne who was betrothed to Fionn mac Cumhaill at the time—that’s a big no-no. They Fianna give chase, and ultimately Diarmuid gets gored to death by a magical boar who’s also his step-brother and then Diarmuid’s step-father, the love god Aengus Óg, temporarily reanimates his step-son’s corpse so they can say their goodbyes.

Don’t you just love Irish myths?

Note: In these later myths the swords have slightly different names—Moralltach (instead of Fraoch Mór) and Beagalltach (instead of Fraoch Beag)—but their meanings remain the same: Great Fury and Little Fury. Unfortunately for Diarmuid, the blades of these swords don’t seem to be as strong or as sharp as they were when they first appeared in the Mythological Cycle. To quote from Irish historian and journalist Standish O’Grady’s 1880 translation of the The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne:

[A]nd thereupon he drew the Beag-altach from the sheath in which it was kept, and struck a heavy stroke thereof upon the wild boar’s back stoutly and full bravely, yet he cut not a single bristle upon him, but made two pieces of his sword.

6. Gorm Glas (Blue Green)

Gorm Glas, the Blue Green, was the sword of the Ulster king Conchobhar mac Nessa. As detailed in Irish folklorist Lady Gregory’s 1902 work Cuchulain of Muirthemne: The Story of the Men of the Red Branch of Ulster, Conchobhar loaned the “great sword” to his son, Fiachra (a.k.a. Fiacra the Fair) along with his enchanted shield Ochain (see below) so that he might go “do bravery and great deeds.” The results were mixed. While Fiachra, Gorm Glas in hand, bravely led the attack on the Red Branch Hostel, he was bested in combat by Iollan, son of Fergus mac Roth (owner of Caladcholg, see above) and was ultimately killed by the Red Branch warrior Conall Cearnach, who famously made the “brain-ball” that would kill Fiachra’s father Conchobhar (see below).

7. Mac An Lúin (Son of the Spear)

Mac An Lúin was the sword of famed Fenian Cycle hero Fionn mac Cumhaill (anglicized as Finn McCool / MacCool). It was said that the sword never had to cut twice, for it killed with every stroke, and Fionn only used it in times of greatest danger. While the sword’s name perhaps suggests a relation to the enchanted spear Lúin Celtchair (see below), Scottish poet James Macpherson presents an alternative origin and name for the sword: “Son of Luno.” Luno was a smith of Lochlin, whom Fionn (Fingal in Macpherson’s Poems of Ossian) chased across the waves for ten days before catching him at the Isle of Skye and forcing him to make the sword. For this reason, Mac An Lúin is also sometimes called “Son of Waves.”

Of course, I’d be remiss not to mention that while Macpherson purported that his poems—first published in 1761 (Fingal) and 1763 (Temora)—were translations of Dark Age-era Gaelic manuscripts…that turned out to be not so true.

8. Orna (Little Pale Green)

The sword of the Fomorian king Tethra, Orna could speak and recount its deeds when unsheathed. After Tethra’s defeat at the second battle of Magh Tuireadh, Orna was picked up by Ogma, the Irish god of eloquence and champion of the Tuath Dé Danann, and the sword proceeded to recount everything it had done while in the hands of its previous owner. Tethra, for his part, went on to rule the Otherworld realm Magh Mell (Plain of Happiness).

However, according to the same source material (re: Whitley Stokes’ 1891 translation of the Cath Maige Tuired), swords talking on the battlefield was a fairly common occurrence in mythological Ireland. There’s even an explanation for why weapons, like Orna, were compelled to speak. And I quote:

“Then the sword [Orna] related whatsoever had been done by it; for it was the custom of swords at that time, when unsheathed, to set forth the deeds that had been done by them. And therefore swords are entitled to the tribute of cleansing them after they have been unsheathed. Hence, also, charms are preserved in swords thenceforward. Now the reason why demons used to speak from weapons at that time was because weapons were worshipped by human beings at that epoch, and the weapons were among the safeguards of that time.”

9. Díoltach (Retaliator)

Along with Fragarach and Fraoch Mór (see both above), Díoltach (Retaliator) was one of the three main swords of the sea-god Manannán mac Lir. The sword “never failed to slay,” according to author Charles Squire’s 1919 book Celtic Myth and Legend.

Manannán mac Lir gave Díoltach to Naoise, a champion of the Red Branch, and in one version of events a rival champion (Eoghain mac Durthacht) took the sword from Naoise and killed him with it at the behest of Conchobhar mac Nessa. In another version of events, Naoise and his two brothers were captured and were to be executed. Since none of the brothers wanted to see the others slain, Naoise offered Díoltach to their executioner, a Norse prince named Maine, who slew all three brothers with one stroke.

Spears From Irish Mythology

10. Birgha (Spit-Spear)

Also known as the Spear of Fiacha (or Fiacail), Birgha was an enchanted, venomous spear. The warrior Fiacha, a follower of Cumal (a leader of the Fianna), gave the spear to Cumal’s son Fionn mac Cumhail so that he might defeat Aillén, an evil creature/former member of the Tuath Dé Danann who resided, three-hundred-and-sixty-four days a year, in the Otherworld. Each and every Samhain the monster—nicknamed “the burner”—would wreak havoc on the royal residence of Tara (also: Teamhair) with his fire-breath after lulling its defenders to sleep with enchanted music. Specifically, Aillén plays—or weaponizes, I should say—the suantraí (lullaby) strain of ancient Irish music, which is frequently deployed by gods, druids, and other musicians in the myths in order to incapacitate opponents.

That’s where Birgha comes into play.

In Lady Gregory’s version of events, Fiacha teaches Fionn how to unlock the power of the spear, instructing his pupil as follows:

“When you will hear the music of the Sidhe, let you strip the covering off the head of the spear and put it to your forehead, and the power of the spear will not let sleep come upon you.”

source: Gods and Fighting Men (1902)

In another version of the story, Fiacha gives the spear to Fionn precisely because he does not know how to use it himself.

Either way, the story ends with Fionn holding Birgha to his forehead and (in some accounts) inhaling its fumes, making him immune to Aillén’s music and allowing him to kill the creature with the spear.

11. Cletiné (Little Spear)

Cletiné was one of Cúchulainn’s many spears, which he used to slay many warriors. Medbh (anglicized as Maeve), queen of Connacht, coveted the little spear and sent a bard, Redg, to request the spear from Cúchulainn on the grounds that one must never refuse a gift requested by a poet. The request angered Cúchulainn so much that instead of handing Cletiné over to the bard, he flung it at him (whoopsie). Here’s what happened next, according to the Joseph Dunn’s 1914 translation of the The Cattle-Raid of Cooley:

“Thereupon Cuchulain hurled the spearlet at him, so that it struck him in the nape of the neck and fell out through his mouth on the ground. And the only words Redg uttered were these, ‘This precious gift is readily ours,’ and his soul separated from his body at the ford.”

And here we find a nice—well, not so nice—example of how Irish myths are often tied up with place-names and geography (as discussed in my article on the differences between myths, legends, folktales, and fairytales). Because as the story goes, after Cú Chulainn spears the bard by the ford, he tosses the busted copper (or umal) from his spear-tip (which presumably broke as a result of the impact with the bard’s spinal column) into the adjacent stream. Henceforth, the stream is known as Uman-Sruth, or Copper Stream. The ford, meanwhile, earns the moniker Ath Solom Shet, or Ford of the Ready Treasure.

12. Del Chliss (Charioteer’s Goad)

According to Ellis, del chliss originally referred to “a split piece of wood” (source: A Dictionary of Irish Mythology) and later became the term used for a charioteer’s goad or spur—a pointed piece of wood for driving horses. The capitalized Del Chliss refers to a spear used by Cú Chulainn, who, in the myths, often fought from his chariot. In his very first battle, Cú Chulainn famously uses Del Chliss to slay the three supernatural sons of Nechtan Scéne, who had boasted of killing more men of Ulster than any other living beings. Cú Chulainn rode away from their fortress with their three severed heads hanging from his chariot.

13. Gae Assail (Spear of Assal)

Also known as the Lightning Spear, or simply Lugh’s Spear, the Gae Assail was one of the Four Treasures or Jewels of the Tuatha Dé Danann (the sword Cliamh Solais was another, see above). To quote from Whitley Stokes’ 1891 translation of the Cath Maige Tuired: “Out of Gorias was brought the Spear that Lugh had. No battle was ever won against it or him who held it in his hand.” The sun-god Lugh, also known as Lugh Lamhfada (“of the long arm” or “of the long throw”) famously used the spear in the second battle of Magh Tuireadh. An enchanted weapon, the Gae Assail never missed its mark, and always returned to its thrower (similar to how Mjölnir returns to Thor in Norse mythology).

14. Gáe Bulg (Belly Spear)

The most famous of Cú Chulainn’s spears, Gáe Bulg (also: Gáe Bulga, Gáe Bolg, Gáe Bolga) originally belonged to the female warrior Scáthach, champion of Alba (Scotland), who ran a military academy on the aptly named Scáthach’s Island (thought to be the Isle of Skye). During Cú Chulainn’s training on the island, Scáthach gifts the Red Branch warrior the spear—but first she teaches him how to throw it…with one foot. Yes, you read that correctly: Rather than being thrown by hand, the Gáe Bulg is cast “from between the fork of the foot,” according to Dunn’s 1914 translation of the The Cattle-Raid of Cooley. But that isn’t even the strangest thing about this weapon.

Also known as the Barbed Spear, the Gáe Bulg makes a single wound when entering the body of an enemy, but once inside, thirty barbs pop open, inflicting gruesome damage. So gruesome, in fact, that the spear “could not be drawn out of a man’s flesh till the flesh had been cut about it.” Yeesh. Being a mythological warrior is messy business…which is probably why Cú Chulainn usually has his trusty sidekick and charioteer, Laeg, take care of the post-killing Gáe Bulg removal in the myths.

Throughout the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, Cú Chulainn uses the spear to kill (amongst others) Loc Mac Mofebis, a champion of Medb; Ferdia, who trained with Cú Chulainn under Scáthach; and even his own son, Conlaí. The spear develops such a reputation that Cú Chulainn’s opponents often flee—or attempt to flee—the battlefield when they hear the hero call for it.

15. Gae-Ruadh (Red Javelin)

Gae-Ruadh was a spear that originally belonged to Manannán mac Lir. It was notable for having two prongs, or two points. As was the case with Fraoch Mór, one of Manannán mac Lir’s swords (see above), Gae-Ruadh—the Red Javelin or Red Spear—showed up in later legends in the hands of Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, who inherited it from the love-god Aengus Óg. Once again, there is a slight name change, but the meaning remains the same: Gáe Dearg (Red Spear).

Note: In Irish historian and journalist Standish O’Grady’s 1880 translation of the The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne, Diarmuid is also seen wielding a yellow spear (Gáe Buide), which he uses (to not such great effect) in his fight against the aforementioned magical boar/step-brother. And I quote:

Then Diarmuid put his small white-coloured ruddy-nailed finger into the silken string of the Ga buidhe, and made a careful cast at the pig, so that he smote him in the fair middle of his face and of his forehead; nevertheless he cut not a single bristle upon him, nor did he give him wound or scratch. Diarmuid’s courage was lessened at that…

16. Lúin Celtchair (Spear of Celtchar)

Often given simply as Lúin, this enchanted, venomous spear (or lance) is discovered on the battlefield after the second Battle of Magh Tuireadh, having belonged to “some chief of the mythic Tuatha-de-Danann race,” to quote William H. Hennessy’s introduction to his 1889 translation of Mesca Ulad, or The Intoxication of the Ultonians. Granted, Lady Gregory asserts in Gods and Fighting Men that the spear actually belonged to the King of Persia. Previous owners aside, what all storytellers can agree on is that Celtchar mac Uthechar, a Red Branch warrior—described as “a grey, tall, very terrible hero of Ulster” in the Story of Mac Dathó’s Pig—eventually claims the spear.

A possible reimagining or “reboot” of the Mythological Cycle’s Gae Assail a.k.a. Lugh’s Spear a.k.a. the Lightning Spear, the Ulster Cycle’s Lúin is notoriously difficult to tame. According to the Irish narrative Togail Bruidne Dá Derga (The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel), upon tasting the blood of an enemy, Lúin writhes in the hands of its owner. If no blood is tasted, the spear must be quenched in a cauldron of venom, lest it turn on its owner and burst into flame. Celtchar ultimately dies from Lúin’s own venom after a drop of blood from a slain enemy inadvertently drips from the spear’s tip onto Celtchar’s flesh.

Shields From Irish Mythology

17. Derg-Druimnech (Red-Backed)

Derg-Druimnech was the shield of Domhnall Breac, king of the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riada (also: Riata) that encompassed parts of northeastern Ireland and the western seaboard of Scotland. During the battle of Moira (also: Moyrath), which was said to have occurred in 637 CE, the Ulster hero Conall Cearnach cast a spear at Domhnall. Here, I’ll let Irish historian P. W. Joyce tell you what happened next:

“[T]he javelin of Conall, which was aimed at King Domnall, passed through three shields interposed by his followers to shelter him, and struck Derg-druimnech (i.e. ‘ red-backed ‘), the golden shield of the monarch himself.”

source: A Social History of Ancient Ireland (1903)

Did you catch that? (No pun intended.) Three warriors placed their shields in front of their king to protect him, but Conall’s spear went through all three shields—and presumably through all three warriors—before becoming embedded in Derg-Druimnech. And while Domhnall is wounded in the attack (the shield does an adequate but not perfect job of protecting him from the spear), the king and his fellow Dál Riada warriors ultimately win the battle.

18. Ochain (Moaner)

Also given as Acéin and sometimes referred to as the “Ear of Beauty,” this enchanted shield belonged to Ulster king Conchobhar mac Nessa. In Whitley Stokes’ translation of the Tidings of Conchobar Mac Nessa (published in Ériu in 1910), it is said of “Ochoin” that “four rims of gold were round it.” The shield famously moaned a warning whenever its bearer was in danger. The three chief waves of Ireland—Tuaithe, Cliodhna, and Rudraidhe—would roar in response to its wails. Along with his sword Gorm Glas (see above), Conchobhar lent the shield to his son Fiachra, who led the attack on the Red Branch Hostel. After Fiachra was bested in combat by Iollan, Ochain moaned a warning, bringing Conall Cearnach to Fiachra’s (temporary) rescue.

Staffs and Slingshots From Irish Mythology

19. Crann-Tabuáll (Staff Sling) & Caer-Clis (Feat Ball)

A favorite weapon of Irish heroes, the staff sling consisted of a long staff with a short sling at one end for hurling projectiles. While the staff slings themselves did not usually have any special significance, the projectiles or “sling shots” often did. A slingshot ball made for a specific purpose was called caer-clis (“feat ball”) or uball-clis (“feat apple”). Lugh used such a ball, called the Tathlum, to kill Balor of the Evil Eye, his grandfather and leader of Tuatha Dé Dannan’s greatest enemies, the marauding Fomorians.

According to Ellis, the Tathlum was made by mixing the blood of toads, bears, and vipers with sea-sand and letting it harden. Another type of caer-clis was a liathróid inchinne, or brain-ball, which was made from the brains of an enemy and hardened with lime. The most famous brain-ball was made by Conall Cernach from the brain of the Leinster king Mesgegra. This brain-ball was stolen by the Connacht warrior Cet mac Mágach and used to kill Conchobar mac Nessa.

20. Lorg Mór (The Great Staff)

Lorg Mór, also known as Lorg Anfaid (The Staff of Wrath), was the weapon of choice of The Dagda, the father of the gods. It has been described as a gigantic magic club, so large that The Dagda dragged it around on wheels. The head of the staff had the power to slay nine enemies in a single blow, while the handle of the staff could revive those slain with a single touch. Or, as it’s described in the medieval Irish manuscript Leabhar Buidhe Leacáin (the Yellow Book of Lecan), the Lorg Mór has a “smooth end” and a “rough end”—one that “slays” and one that “brings the dead back to life.”

Based on these life-giving (and -taking) properties, anthropology and linguistics professor Garrett S. Olmsted found parallels between the Lorg Mór and weapons from other mythologies. And I quote:

“In India, Índraḥ, the controller of the Middle Region, has an ańkuśáḥ [ankusha] ‘hook, goad’ which accomplishes the same thing as the Dagda’s staff. In Scandinavia, Thórr [Thor], the son of the controller of the Upper Realm, controls the hammer Mjǫllnir [Mjölnir] with the same properties as the ańkuśáḥ.”

source: The Gods of the Celts and the Indo-Europeans (1994)

Olmsted also reveals that in the Yellow Book of Lecan, a description of the Lorg Mór is given that might change the way we picture this weapon in our minds. To quote Olmsted’s translation:

(The Dagda had) behind him a forked branch with a wheel (gabol gicca rothach) which required eight men (to pull it), so that its track after him was enough for the boundary ditch of a province.

According to Olmstead, the forked club or gabal-lorg described here is “undoubtedly the same device” as the Lorg Mór. Which means, yes: much like Poseidon and his trident from Greek mythology, the weapon of choice of one of Irish mythology’s greatest gods…is a big fork.

In Conclusion…

Let’s go, people!

We need more authors and screenwriters penning Irish- and Celtic-mythology inspired books and movies.

There is so much existing lore already surrounding these mythical Irish weapons, the storylines basically write themselves.

Unfortunately, my pipe dream of seeing the Irish gods (a.k.a. the Tuatha Dé Danann) join the Marvel Cinematic Universe was unceremoniously flushed with the release of Thor: Love and Thunder, a film that could have introduced/included a plethora of pantheons—but didn’t.

I even did two rounds of fan-casting (see below):

But I digress.

The future of Irish and Celtic folklore-inspired fiction is undoubtedly bright.

And I plan to contribute to this collective fascination with Celtic fantasy by continuing to make my silly lists.

Follow along, if you’d like.

Want to help keep the (neon green) lights on?

…while also enjoying some incredible Irish and Celtic mythology-inspired short fiction? Check out:

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes by Philip Freeman (narrated by Gerard Doyle). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 7.5-hour audiobook for free.