Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

[Note: Read parts 1 – 3 if you haven’t already! >> “1) Was the Irish Hero Cú Chulainn Actually a Comet?“ / 2) The Science Behind the “Cú Chulainn Was a Comet” Theory / 3) Does History Support the Theory That Cú Chulainn Was a Comet?

One of the greatest things the cosmic Cú Chulainn theory has going for it is that its founder, Mike Baillie, was reluctant to make the connection between Irish mythology and the event of 536 CE.

This wasn’t a case where one of the ancient aliens guys was like “Oh, yeah, it’s probably aliens.”

Instead, this was a scientist who, in the years before ice core samples would shed new light on the subject, was at his wits’ end trying to figure out what the heck his tree-ring chronology was trying to tell him.

Turns out, it kept leading him to the same place…

A Comet in King Arthur’s Court

First and foremost, there’s that passage from the Annales Cambriae, which tells of a battle at Camlann in the year 537 during which Arthur and his nemesis Medraut (a.k.a. Mordred) “fell,” and following which there was “great mortality in Britain and Ireland.”

Given how closely that “great mortality” lines up with what we already know about the year 536 and the years that followed, some have interpreted this passage as historical—and, thus, proof of Arthur’s historicity.

But that’s neither here nor there.

What’s interesting about the lore surrounding Arthur’s death is that it’s focused on this concept of a wasteland, a Celtic motif in which the barrenness and inhospitality of a place is tied to a specific character—in this case, the Fisher King a.k.a. the Maimed King a.k.a. the Wounded King who, like the land, was rendered infertile.

So the question is: was this legendary wasteland inspired by an actual comet strike?

Because Merlin does prophesy the birth of Arthur using a comet as his guide.

Here’s how Geoffrey of Monmouth, the 12th-century Welsh cleric who helped make King Arthur a household name, described the comet:

“There appeared a star of great magnitude and brilliance, with a single beam shining from it. At the end of this beam was a ball of fire, spread out in the shape of a dragon.”

It’s also been argued that Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon—whose name can be translated to “Terrible Head of Dragons”—took his name from the same dragon-shaped comet.

And according to journalist Edwin Emerson, that comet was none-other than Halley’s Comet making its 530 CE fly-by—although that timing doesn’t really work out if Arthur is to fall in battle in 536.

But still, considering we’re dealing with myth and legend, we don’t have to be sticklers about dates. Because it’s possible the appearance of Halley’s Comet still helped inspire the original story even if the narrative timeline was ultimately altered.

Turns out that was par for the course in the 6th century.

Something Hairy This Way Comes

Since at least the 6th century, comets have been associated with plague, famine, and war.

We know this thanks to bishop and scholar Isidore of Seville. Born sometime in the mid-6th century, Isidore wrote an illuminating (hair-rising?) entry for the word “comet” in his Etymologies. And I quote:

“A comet (cometa) is a star, so named because it spreads out the ‘hair’ (coma) of its light. When this type of star appears it signifies plague, famine, or war. Comets are called crinitae in Latin, because they spread their flames like hair (crines).”

Echoing these ideas was the English monk/scholar Bede (a.k.a. The Venerable Bede), born in the late-7th century. In his On the Nature of Things, Bede wrote the following:

“Comets are stars with flames like hair. They are born suddenly, portending a change of royal power or plague or wars or winds and heat.”

Now seems like a good time to mention that King Arthur is sometimes described as having flaming red hair, fulfilling a folkloric prophecy that a redhead would lead the country in times of trouble.

And now also seems like a great time to describe Cú Chulainn’s hair in more detail because, hew boy, is it wild.

To quote Thomas Kinsella’s translation of the Táin Bó Cúailnge (or, the Cattle Raid of Cooley):

“You would think he had three distinct heads of hair—brown at the base, blood-red in the middle, and a crown of golden yellow. This hair was settled strikingly into three coils on the cleft at the back of his head. Each long loose-flowing strand hung down in shining splendour over his shoulders, deep-gold and beautiful and fine as a thread of gold. A hundred neat red-gold curls shone darkly on his neck, and his head was covered with a hundred crimson threads matted with gems.”

I mean, is that a description of a guy with a comet tail for hair or what?

It gets weirder, too. Because if you’re not familiar with Cú Chulainn, during battle he enters this rage-state known as the ríastrad (often translated as “warm-spasm” or “battle-frenzy”). While in this state, Cú Chulainn nearly doubles in height, one of his eyes bulges out of its socket, his forehead splits open and starts spraying blood…

Oh, right, then there’s his hair.

To quote The Táin.

“The hair of his head twisted like the tangle of a red thornbush stuck in a gap; if a royal apple tree with all its kingly fruit were shaken above him, scarce an apple would reach the ground but each would be spiked on a bristle of his hair as it stood up on his scalp with rage.”

Imagine Cú Chulainn’s head going full porcupine—and now imagine what that would look like on a cosmic scale.

Sort of like an explosion, right? A firework.

So is it possible that the description of Cú Chulainn entering his war-spasm state is really a metaphor for a comet a.k.a. a “hairy star” breaking apart and exploding in the atmosphere?

Uhhh…maybe?

Again, the timing doesn’t really work out storywise because according to Osborne-McKnight, the Ulster Cycle (a.k.a. Red Branch Cycle) of Irish mythology, the cycle that stars Cú Chulainn, is set primarily during the late part of the first century BCE.

While Halley’s Comet did pass by the Earth in 12 BCE, the myths of ancient Ireland wouldn’t be written down until the arrival of Christianity in the fifth century CE.

And it really wasn’t until the start of the sixth century CE that monasteries started being built in Ireland and thus, it was that 530 passage of Halley’s Comet that would have been perfectly suited to observation.

It’s an event that, perhaps, would have been top-of-mind for Irish scribes as they were putting down tales of Cú Chulainn and his father Lugh.

Because of course we can’t forget about Lugh. He’s the third piece of this cosmic trifecta.

A Star Is Born

The god of many talents and namesake of the cross-quarter day, Lughnasa, Lugh was in many ways the original hero of Irish mythology, showing up on the scene during the Mythological Cycle to free the Tuatha Dé Dannan from the oppressive Fomorians, who, incidentally, were led by Lugh’s grandfather, Balor of the Evil Eye.

When Lugh first appears he’s as bright as a star, but traveling in the wrong direction for the sun. To quote from The Fate of the Children of Turenn:

“Then arose Breas, the son of Balar, and he said: ‘It is a wonder to me’, said he, ‘that the sun to rise in the west today, and in the east every other day’. ‘It would be better that it wer so’, said the Druids. ‘What else is it?’ said he. ‘The radiance of the face of Lugh of the Long Arms’, said they.”

So, what has a face like the sun and some long arms?

Could be a comet.

What’s more, Lugh is sometimes described as having hair the color of fire, although usually depicted with blond, curly hair.

Physical features aside, what really sets Lugh apart from the other Irish gods of the Mythological Cycle is his weaponry.

Lugh is famed for his use of projectiles, an innovation at the time—that time being approximately 2,000 BCE, according to the Annals of the Four Masters.

In addition to sending a special slingshot ball called the Tathlum (made from sea-sand mixed with the blood of vipers, bears, and toads) right through his grandfather Balor’s giant, fiery eye during the second battle of Cath Maige Tuired, Lugh expertly tosses the Gae Assail a.k.a. the Lightning Spear, taking out dozens (hundreds?) of Fomorians.

The spear, sometimes described as one of the Four Treasures or Jewels of the Tuatha Dé Danann, can fly around the battlefield on its own, never missing its marks, and, like Mjölnir, it automatically (automagically?) returns to the hand of its thrower.

The spear is sometimes conflated with Areadbhair, which, before being brought to Lugh, courtesy of the sons of Turenn, had belonged to the King of Persia, Pisear. The spear needed to be stored in water lest it burst into flame.

Lugh’s son Cú Chulainn, sometimes seen as a reincarnation of Lugh himself, inherits his father’s penchant for hurling enchanted spears.

In Cú Chulainn’s case, the Gáe Bulg a.k.a. the Barbed Spear is thrown with the foot for some reason and once it pierces its target, 30 barbs pop open inflicting horrific damage.

Again we have that porcupine-esque imagery, with the barbs exploding out.

Another veiled reference to a comet or comet fragment bursting in the upper atmosphere, perhaps?

And while we’re on the subject of wicked and wondrous weapons, King Arthur’s sword was once described as having two chimeras on the hilt, and “when the sword was unsheathed what was seen from the mouths of the two chimeras was like two flames of fire, so dreadful that it was not easy for anyone to look.”

No, chimeras aren’t technically dragons, but come on they’re basically dragons, so there could be a connection between this imagery and the aforementioned dragon-shaped comet.

And the overall effect of Arthur’s sword being too bright to look at definitely gives off Lugh-of-the-shining countenance vibes and could similarly be a reference to an approaching celestial body—namely, Halley’s Comet.

The Comet That Launched a Thousand Myths

Indeed, the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 530 and the subsequent global devastation—whether the two were directly related or not—may have inspired stories of dragons and fiery weapons and wastelands across Eurasia.

In China, for example, it was noted that dragons fought in ponds, and trees were broken by a passing dragon during the the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 530. Many at the time believed the “dragon” was connected to the decline of the dynasty.

Speaking of decline, I’m sure most of you are already familiar with the Norse mythological concept of Ragnarok, during which the Midgard serpent Jörmungandr is described as spraying venom through the air and thrashing around in the sea, creating huge swells.

Oh, right, and Thor kills the serpent but not before the serpent fatally wounds him.

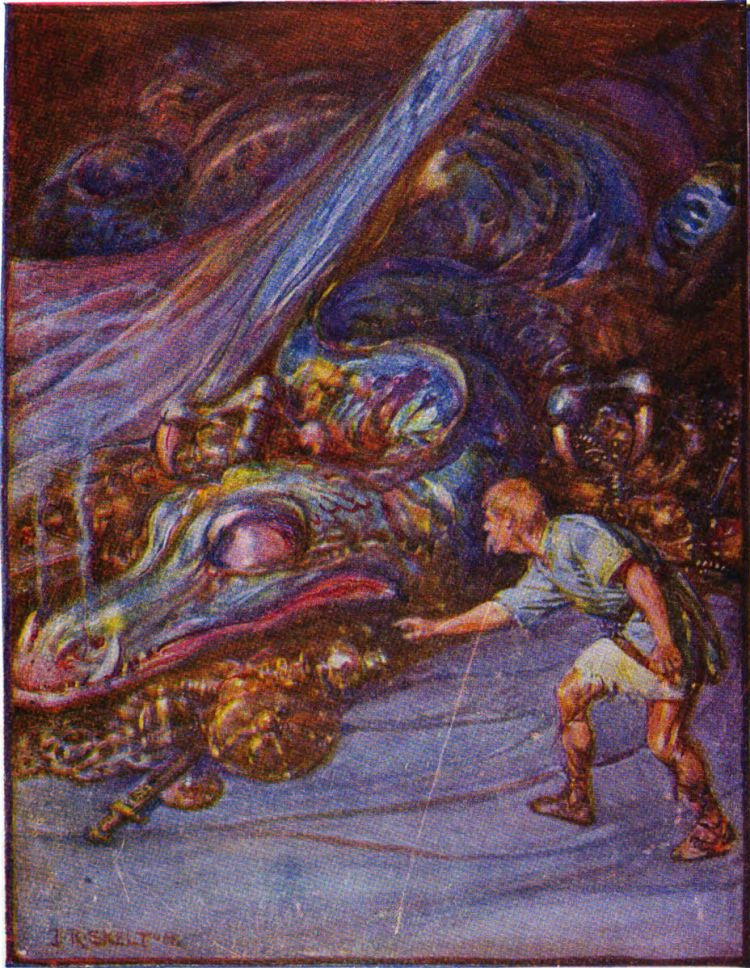

Then there’s the Beowulf saga, which features the “night-goer” Grendel who lives in a misty marsh and of whom it is said, “Every nail, claw-scale and spur, every spike / and welt on the hand of that heathen brute / was like barbed steel.”

Because weapons can’t pierce Grendel’s skin, all anyone can do is sit around and wait to get attacked. That is until a weaponless Beowulf rips his arm off. Then Beowulf discovers Grendel’s home, which he shares with his mother, at the bottom of a monster-infested lake and yadda, yadda, yadda, decades later a fire-breathing dragon emerges and starts torching the kingdom.

Yes, in the end, Beowulf kills the dragon, but not before the dragon fatally wounds him.

Interestingly, some scholars believe the Beowulf saga was inspired by the Táin Bó Fráech (or Cattle Raid of Fráech) from the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology.

In the myth, Queen Medb of Connacht tricks Fráech into swimming in a monster-infested river. Unarmed, the hero is forced to battle a péist (i.e. a serpent or dragon) with his bare hands and in this case, ruh-roh, the péist rips the hero’s arm off.

Ultimately, Fráech is given a sword and kills the péist, but not before the péist has fatally wounded him.

Fortunately, in one version of this myth, before Fráech can kick the bucket, a hundred and fifty sídhe (a.k.a. fairy) maidens appear and carry him through the Cave of Cruachan to the Otherworld where all of his wounds are miraculously healed.

Which is not too dissimilar from how, according to legend, Morgan le Fay (a.k.a. Morgan the Fairy) brings King Arthur to the mystical island of Avalon to be healed after he falls in the battle of Camlann.

Whoa.

There is definitely some storytelling symmetry going on here.

But at the same time, these potentially shared cosmic origins highlight one of if not the most confusing aspects of the cosmic Cú Chulainn theory:

Is the Comet the Good Guy or the Bad Guy?

Because even the most amateur of yarnspinners would tell you that in a story where a strange fireball appears in the sky and explodes, plunging the world into a “nuclear” winter that leads to millions of deaths…the comet would be the bad guy.

So maybe we have things the wrong way around.

Maybe Halley’s Comet isn’t Lugh or Cú Chulainn, it’s Balor of the Evil Eye. I mean, come on—the dude has a giant eyeball that spews fire and can incinerate countrysides. His name means “the flashing one.” He’s basically a comet with legs.

And that means Lugh represents…the sun. Which has always been his traditional interpretation anyway.

And more specifically, perhaps Lugh’s hero archetype represents the sun reemerging to restore and rejuvenate the wasteland. His arrival and/or sacrifice marks the beginning of a new era. A changing of the guard.

Viewed through this lens, King Arthur with his fiery hair and shining sword is the sun. Mordred, Arthur’s traitorous nephew and architect of his downfall, is the comet.

Thor? The sun. The world serpent? The comet.

Beowulf? The sun. The dragon and Grendel? The comet and a comet fragment, maybe?

As for Cú Chulainn and his spiky hair and spiky spear, just imagine a sixth-century Irish storyteller pointing up at the sky at an exploding comet fragment and saying, “Oh yeah, there’s Cú Chulainn up there, kicking some butt.”

The hero isn’t the comet itself, but the comet exploding like a firework is the result of the hero’s handiwork.

And while I’ve always described Cú Chulainn as the Irish Incredible Hulk, maybe he’s more like the Irish Superman, getting his power from the sun.

Case in point: the story of Cú Chulainn’s death.

The Death of (Irish) Superman

After Lugaid mac Con Roí, a.k.a. Lugaid Son of Three Hounds—who, along with Queen Medb, had been an architect of Cú Chulainn’s downfall—fatally wounds Cú Chulainn with a magical spear, he beheads him.

Big mistake.

A burning “hero-light” surrounds Cú Chulainn’s body, and suddenly our hero’s sword is falling—woops, there goes Lugaid’s hand. Chopped off by the sword of a slain warrior.

A new hero, Conall Cernach, then takes center stage, pursuing Lugaid and fighting him with one hand tucked into his belt so as to not have an unfair advantage.

Long story short, Conall kills Lugaid, chops off his head, brings it back to Red Branch headquarters a.k.a. Emain Macha, sets it on a stone, and here’s where things get really interesting because Lugaid’s decapitated head melts through the stone and falls right through it.

Lugaid is the comet.

Cú Chulainn is the sun.

Or at least that’s one interpretation.

What do you think?

P.S. Hope you had a great Lughnasa!

Get the low-down on the August 1st feast over at the IrishMyths YouTube channel:

Want to learn about the darker side of Irish mythology? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Irish Monsters in Your Pocket

In the Ireland of myth and legend, “spooky season” is every season. Spirits roam the countryside, hovering above the bogs. Werewolves lope through forests under full moons. Dragons lurk beneath the waves. Granted, there’s no denying that Samhain (Halloween’s Celtic predecessor) tends to bring out some of the island’s biggest, baddest monsters. Prepare yourself for (educational) encounters with Irish cryptids, demons, ghouls, goblins, and other supernatural beings. Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes by Philip Freeman (narrated by Gerard Doyle). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 7.5-hour audiobook for free.