Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Cernunnos.

Even if you’ve never heard that name before, I can guarantee you recognize the Celtic deity to whom it belongs.

Thanks in large part to his absorption into modern, neopagan religious practices, Cernunnos, whose name means “the horned one,” has become a mascot of sorts for Celtic mythology.

But to clarify—and this is an important clarification—Cernunnos is not an Irish god.

He’s Gaulish. Or “Gallo-Roman.”

By which I mean Cernunnos was originally worshiped in ancient Gaul by Celtic-speaking peoples as early as the fifth century BCE (if not earlier), and that worship continued well after the Roman conquest of Gaul in the first century BCE.

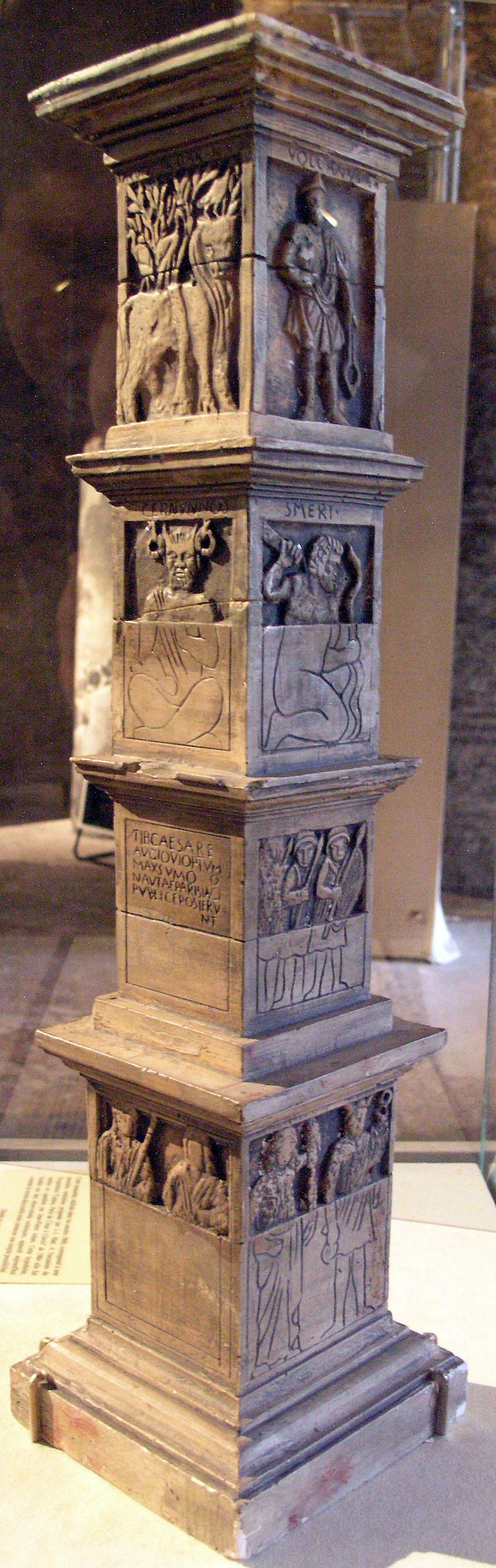

Indeed, depictions of Cernunnos from the Roman era often find him grouped together with Greco-Roman deities, most notably on the Pillar of the Boatmen, where he appears alongside (or rather, on top of) Jupiter, Vulcan, Mars, and Mercury, amongst other figures.

The pillar, which was erected during the first century CE in what is now Paris, France, also happens to provide the only undisputed instance of the name Cernunnos from ancient times.

Thus, it has been used as a key of sorts for identifying other possible depictions of the horned god, including one from Reims, France; one from the Romano-British settlement of Corinium (modern day Cirencester); and, perhaps most famously, one from the Gundestrup cauldron, which was discovered in Denmark.

FYI: You can see all of the aforementioned depictions of Cernunnos (and more) in the video adaptation of this essay below.

Now, at this point I could go into excruciating detail about the differences between Celtic mythology and Irish mythology, but I already did that in an earlier post/video. And you better believe I used the depiction of Cernunnos from the Gundestrup cauldron to represent the Celtic side of the equation.

Or, non-equation, as it were.

Because the one thing you really need to understand for the purposes of this video is that Gaulish deities and Irish deities belong to two distinct pantheons.

True, both fall under the “Celtic” umbrella, as both pantheons originated with Celtic-speaking peoples, the Gauls and the Gaels, respectively, and also true, there appear to be some cognates or similar deities within these pantheons, hinting at a shared (albeit distant) origin, which makes sense given the shared linguistic origin (proto-Celtic), but at the end of the day…

They’re different.

And, despite what you may have read on Reddit (we’ll get into it), there is no Irish version of Cernunnos.

The Irish pantheon simply does not have a horned god…or does it?

That’s what we’re going to investigate.

But first, for all you Celtic mythology superfans out there, might I humbly recommend the short story collection Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy, and in particular the story “Cave Canem” by Ed Ahern, which offers a modern take on a certain horned someone.

The Uindos / Fionn mac Cumhaill / Cernunnos Connection

There’s an odd little passage floating around Reddit and Facebook and other corners of the Internet that claims there are “Old Irish stories [that] describe Cernunnos under the name of Uindos and as the son of the High King of Ireland named Lugh.”

A few things to unpack here.

First and foremost: there is no Irish god or character of any kind bearing the name Uindos in any of the medieval Irish texts in which the Irish myths were first recorded. Sooo there’s that.

Second, and admittedly this one’s more of a quibble, but referring to Lugh as a High King of Ireland is a bit reductionist. Yes, in the myths he is king, for a time, but Lugh is also a god, the god of many talents. What’s more, he’s the savior of the “good” Irish gods, if you will, the Tuatha Dé Danann, leading them into battle against his grandfather Balor of the Evil Eye and the monstrous Fomorians.

Speaking of Lugh’s family tree, he does have a son, two, actually, but neither are named Uindos. Instead, Lugh’s sons are Ibic of the horses and the famed Irish hero Cú Chulainn.

The closest thing I could find to an authoritative source for the Uindos/Cernunnos theory is the book The Truth about Druids, in which author Tadhg MacCrossan defines Uindos as:

“An ancient Celtic god, son of Noudons, in a group of great epic tales and romances called the Fenian cycle. Uindos is also called Cernunnos ([in] Greek). Most famous incarnation is as Finn Mac Cumhail.”

Sooo in this version of the theory, Uindos has a different dad, the British-Celtic god Nodens, who is likely cognate with the Irish god Nuada.

But this inconsistency in parentage doesn’t bother me so much as the assertion that Cernunnos is the *Greek* name of this hypothetical deity Uindos, when we know with a high degree of certainty that Cernunnos is a Latinization of the Gaulish Karnonos, which in turn is derived from the root word karnon, meaning “horn” or “antler.”

Attempting to connect Cernunnos to the Irish hero Fionn mac Cumhaill does make at least some sense, as Fionn, as described in the myths, is an accomplished hunter. This has led some scholars to identify Fionn as a so-called leader of the Wild Hunt, the Wild Hunt being a folklore motif that occurs across European cultures.

Cernunnos, meanwhile, given that he is often depicted alongside stags and ram-headed serpents, is sometimes identified as the Lord of Wild Things or the Lord of the Animals.

But while it’s easy to conflate the two, the Leader of the Wild Hunt and the Lord of the Wild Things represent two different and in some ways opposite motifs. The former sees a mythical figure leading a hunting party in a violent chase, while the latter depicts a mythical figure, in a zen-like pose, taming or protecting wild animals.

What these motifs most definitely have in common is that they were both applied retroactively to the figures in question. And ultimately, I think that’s the best explanation for where this unattested Uindos figure comes from: It’s a modern, neopagan creation that attempts to reconcile or combine these two mythical forces.

That being said, Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warrior band, the Fianna, are, in the myths, associated with a horn: the famed Dord Fiann, the hunting horn of the Fianna, which, depending on the context, can be used either to gather Irish warriors to the battlefield or to rouse Fionn from his eternal slumber.

So while the Irish Fionn doesn’t have horns on his head like the Gaulish Cernunnos, an argument can be made that he is, nonetheless, a “horned” hero.

The Derg Corra / Cernunnos Connection

Staying within the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology, there is another character who is, arguably, a much better fit for the role of Cernunnos-counterpart: Derg Corra, son of Ua Daigre.

This relatively obscure character appears in just one relatively obscure story, “Finn and the Man in the Tree,” a story that kicks off with your classic Celtic love triangle.

The hero Fionn mac Cumhaill desires a beautiful maiden, but the beautiful maiden desires one of Fionn’s servants, Derg Corra.

Not wanting to upset Fionn, Derg refuses the maiden’s advances. But then the maiden gets upset and implores Fionn to kill him. So Derg goes into exile in the woods and, after the agreed-upon three-day truce, Fionn comes after him.

Here’s what happens next:

“One day as Finn was in the wood seeking him he saw a man in the top of a tree, a blackbird on his right shoulder and in his left hand a white vessel of bronze, filled with water, in which was a skittish trout, and a stag at the foot of the tree. And this was the practice of the man, cracking nuts; and he would give half the kernel of a nut to the blackbird that was on his right shoulder while he would himself eat the other half; and he would take an apple out of the bronze vessel that was in his left hand, divide it in two, throw one half to the stag that was at the foot of the tree, and then eat the other half himself. And on it he would drink a sip of the water in the bronze vessel that was in his hand, so that he and the trout and the stag and the blackbird drank together.”

Now that imagery definitely gives off Cernunnos vibes, especially when you consider the Gaulish god is sometimes depicted with a cornucopia, or horn of plenty.

So while our man in the tree Derg Corra doesn’t have horns on his head, he does have that bronze vessel, which provides sustenance not only for himself but for his furry, feathered, and scale-covered friends as well.

Then, there’s his name: Derg can be translated as red, and Corr as point or peak. Again, not quite a horn, but the word is perhaps suggestive of one.

Granted, Corr can also mean heron or crane, so there’s really nothing conclusive here.

And while the Lord of the Wild Things motif vibes certainly seem strong, there are other explanations for this man in the tree imagery.

For example, there’s the Wild Man of the Woods motif, which has been applied to characters including the Irish Suibhne Geilt (Mad Sweeney), the Scottish Lailoken, the Welsh Myrddin Wyllt, and, later, Merlin of Arthurian Legend fame.

There’s also Celtic scholar William Sayers’s theory that Derg Corra effectively creates or becomes a world tree, “complete with various insignia of the tripartite cosmos as conceived in early Irish thought.”

The Conall Cernach / Cernunnos Connection

Moving backward chronologically to an earlier cycle of Irish mythology, the Ulster Cycle, we find another contender for the Irish Cernunnos crown: Conall Cernach, the famed Red Branch warrior and foster brother of Cú Chulainn.

And right off the bat (hurling stick?), we have a possible etymological connection to Cernunnos. Because while Cernach is often interpreted as “of the victories” or “triumphant,” the presence of the root “cern” has led some scholars to believe there is something horny about his name. Wait, that’s not what I—

However, considering that Conall is never described as having horns in the myths, it’s possible that Cernach is a reference to the hero’s tough, horn-like skin. There’s also the following explanation, courtesy of the scholar J. A. MacCulloch:

“[T]he name Cernunnos signifies ‘the horned one,’ from cernu, ‘horn,’ a word found in Conall’s epithet Cernach. But this was not given him because he was horned, but because of the angular shape of his head, the angle (cern) being the result of a blow.”

Epithet aside, there’s a specific passage in the Táin Bó Fraích (Cattle Raid on Fraech) that hints at a possible Conall-Cernunnos connection. The passage finds Conall in the Alps assisting the titular Fraech in the rescue of his wife, three sons, and cattle.

Alas, they come across a dún or fort in which Fraech’s family is being held. Guarding that fort? A vicious serpent.

An epic showdown seems imminent.

The snake darts forward…and proceeds to wrap itself around Conall’s waist.

Connal wears the snake like a belt as he and Fraech take the fort.

When the rescue and requisite plundering are complete, Connal removes his snake-belt and lets the creature slither away unharmed.

In the scheme of things, this is a small detail. But given that serpents are super common in depictions of Cernunnos, and are sometimes even shown coiled around the god’s waist, it’s a detail worthy of our consideration.

The Dagda / Cernunnos Connection

Finally, let us turn our attention to perhaps the strongest contender for an Irish Cernunnos equivalent: The Dagda, the so-called father of the Irish gods.

As the wielder of a massive club or staff (the Lorg Mór) and possessor of a cauldron (the Coire ansic) from which, it is said, no company ever departs unsatisfied, the Dagda has traditionally been linked to the Gaulish Sucellus, a god who is regularly depicted with a long-handled mallet in one hand and an olla, a jar or barrel for cooking and storing food, in the other.

But in the saga text the Cath Maige Tuired, the second battle of Moytura, which is part of the earliest cycle of Irish mythology, the Mythological Cycle, a curious thing happens:

When the daughter of the Fomorian king Indech asks the Dadga for his name, he replies with a string of names, the very first of which is…

Fer Benn; the Horned Man.

I mean, case closed, right?

Here we have actual, textual evidence of an Irish god with horns.

Only…it’s not that simple.

Because while fer means “man” in Old Irish and Benn can mean the “horn of an animal,” the latter can also mean “peak” or “pinnacle.”

And when we consider the context of the scene, it becomes clear that the Dagda—regardless of whether he’s referring to himself as the horned man, or the peaked man, or the man of pinnacles—is not being literal; he’s being facetious.

“Horned,” in this case, means…horny. Or rather, the Dagda is using the term as a euphemism for a state of male arousal.

To quote from the text, just a few lines before he gives the first of his many names:

“As he went along he saw a girl in front of him, a good-looking young woman with an excellent figure, her hair in beautiful tresses. The Dagda desired her, but he was impotent on account of his belly.”

And now listen to what the young woman replies after the Dagda gives the name Fer Benn:

“That name is too much!”

Joke made; joke understood. Well played, the Dagda.

Our conclusion thus must be that the Dagda is not a horned god in the sense that Cernunnos is a horned god.

As for other potential similarities between the two Celtic deities, some have suggested that both the Dagda and Cerunnuos are representations of what folklorist and anthropologist James George Frazer refers to as the Divine King, a being who embodies the essences of both winter and summer, death and life. It’s essentially the Holly King and the Oak King merged into one entity.

I explore this concept in more detail in my post/video, The Case for a Celtic Santa Claus, where I also happen to explain how the Dagda got his aforementioned big belly that prevents him from, uh, performing.

But once again, I must provide the huge caveat that the Oak King/Holly King interpretations of the Dagda and Cernunnos are modern. They have been applied retroactively, and are not attested to directly in any actual texts or engravings.

The Saint Ciarán / Cernunnos Connection

The bottom line: Irish mythology does not have its own version of Cernunnos.

Irish hagiography, however, is another matter, as some scholars believe stories about Saint Ciarán, a saint known for communing with wild animals, were based, at least in part, on Cernunnos.

And what—or should I say who—do we find carved into the North Cross at Clonmacnoise, the Irish monastery founded by Saint Ciarán?

Well, I’ll let you be the judge.

Want to learn about the darker side of Irish and Celtic mythology? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Irish Monsters in Your Pocket

In the Ireland of myth and legend, “spooky season” is every season. Spirits roam the countryside, hovering above the bogs. Werewolves lope through forests under full moons. Dragons lurk beneath the waves. Granted, there’s no denying that Samhain (Halloween’s Celtic predecessor) tends to bring out some of the island’s biggest, baddest monsters. Prepare yourself for (educational) encounters with Irish cryptids, demons, ghouls, goblins, and other supernatural beings. Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes by Philip Freeman (narrated by Gerard Doyle). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 7.5-hour audiobook for free.