Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Classical historians spent a lot more time writing about men than they did about women. Before I contribute anything else to the conversation about the presence and roles of female druids in ancient Celtic societies, I need to reiterate that important caveat: There just isn’t a lot of text to work with here—at least not when you go waaay back, and not when you compare it to what was written about male druids.

Julius Caesar, for example, could have referenced female druids in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (originally published between 58 and 49 BCE), but he didn’t. He wrote meticulously about the functions of druids, describing them not only as preacher-philosophers, but also as judges who “have opinions to give on almost all disputes involving tribes or individuals, and if any crime is committed, any murder done, or if there is contention about a will or the boundaries of some property, they are the people who investigate the matter and establish rewards and punishments.” He also had time to float the idea that druidism was an import from Britain, writing:

[T]he doctrine of the Druids was invented in Britain and was brought from there to Gaul; even today those who want to study the doctrine in greater detail usually go to Britain to learn there.

Is that actually true? Maybe. Maybe not. But the point here is that Caesar didn’t mention any female druids—or if he did, they were later edited out.

That’s not to say there are no historical references to druidesses from back in ancient times. Look no further than Plutarch, Greek philosopher born in 46 CE.

There arose a very grievous and irreconcilable contention among the Celts, before they passed over the Alps to inhabit that tract of Italy which now they inhabit, which proceeded to a civil war. The women placing themselves between the armies, took up the controversies, argued them so accurately, and determined them so impartially, that an admirable friendly correspondence and general amity ensued, both civil and domestic. Hence the Celts made it their practice to take women into consultation about peace or war, and to use them as mediators in any controversies that arose between them and their allies. In the league therefore made with Hannibal, the writing runs thus: If the Celts take occasion of quarrelling with the Carthaginians, the governors and generals of the Carthaginians in Spain shall decide the controversy; but if the Carthaginians accuse the Celts, the Celtic women shall be judges.

source: Mulierum virtutes (circa 100 CE)

What does that description sound like to you? No, Plutarch doesn’t actually use the term “druid” or “druidess”, but he’s clearly describing the druids of previous writers, the druids of Caesar and Strabo, the latter of whom noted the following:

“The belief in the justice [of the druids] is so great that the decision both of public and private disputes is referred to them; and they have before now, by their decision, prevented armies from engaging when drawn up in battle-array against each other.”

source: Geographica (The Geography of Strabo)

Female Druids in the Archeological Record

The ancient Celts notoriously didn’t write much down, which meant the druids passed on all of their judicial, religious, medicinal, and astronomical knowledge orally. Training to become a druid, which could take up to twenty years (and which perhaps took place in Britain), thus required incredible feats of memory. The bar was set high, but remember: druids belonged to an elite class in ancient Celtic society and, in some cases, wielded more power than kings and chieftains.

So it stands to reason that druids, upon their deaths, would have been buried in ceremonial chambers with lots of gold and jewels and other precious items, yeah?

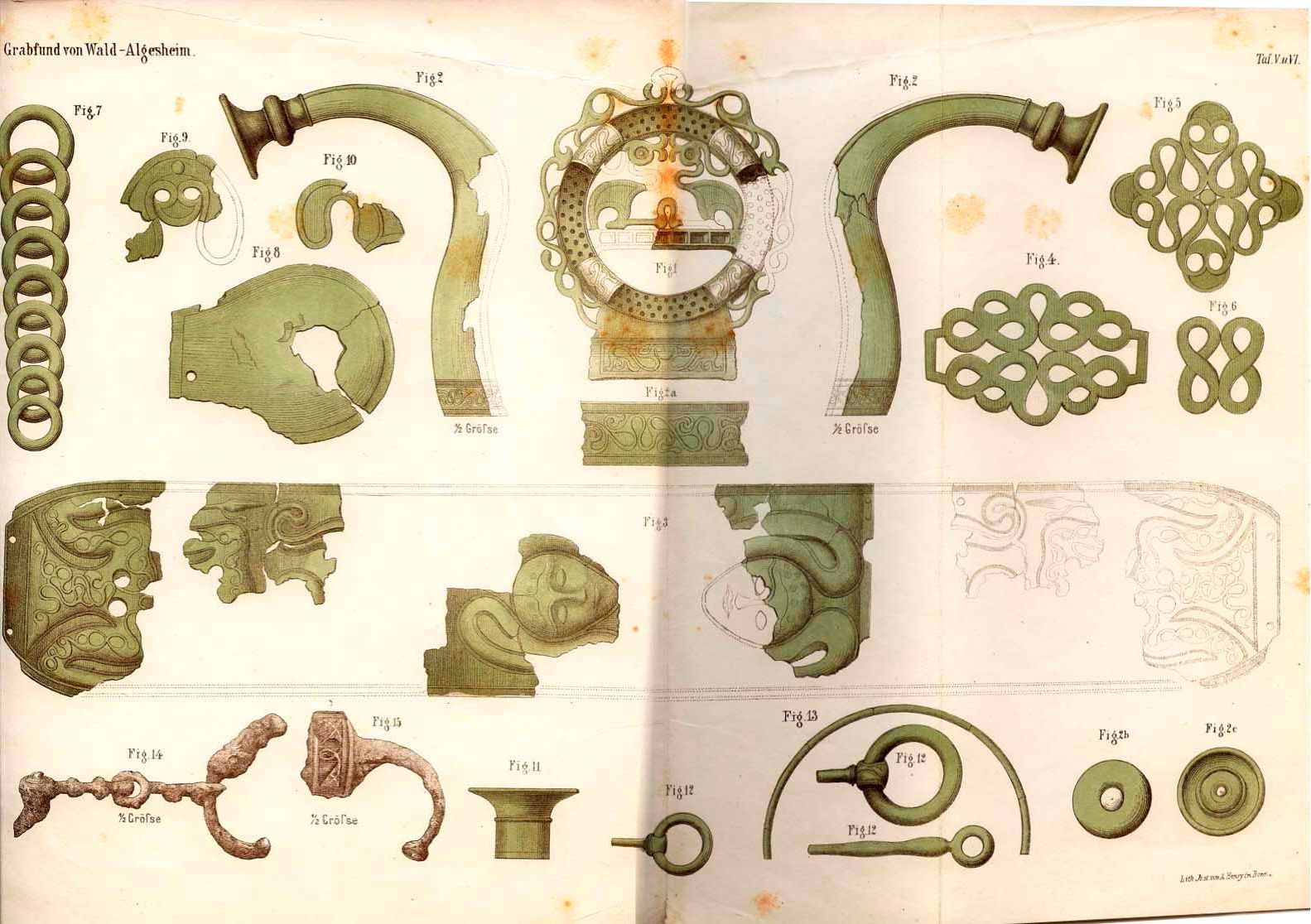

That’s pretty much the argument some people make when talking about France’s Vix Grave and Germany’s Waldalgesheimer chariot burial, two lavishly appointed ancient Celtic grave sites with what appear to be female occupants.

Vix is the older of the two sites, dating all the way back to 500 BCE. Its occupant, who is sometimes referred to as “Lady Vix”, or “Queen Vix”, or in some cases, yes, “Priestess Vix”, was found inside a fifteen-meter-tall palace with, amongst other things, a 24-carat gold torc, a funerary wagon wheel, and the Vix krater—the biggest metal vessel from all of Western classical antiquity.

The woman in the Vix grave was believed to be between 30 and 35 years old at the time of her death, which seems a tad young for druid status. Then again, if druid training began in one’s youth, it’s certainly plausible. Still, there’s nothing in “Priestess” Vix’s tomb that distinguishes her as a Celtic priestess. All the jewelry and other treasure points to her having been a high-status individual, but it’s just as (if not more) likely that she was a Celtic princess or queen.

Now, onto round two: was the woman from the Waldalgesheimer chariot burial a princess or a druidess? As was the case with “Priestess” Vix, the female remains uncovered at the Waldalgesheimer site were found buried with a golden torc, a large metal bucket, and all manner of treasure. This time, however, a two-wheeled chariot dominated the display (hence the name Waldalgesheimer chariot burial).

Once again, some folks conclude from these findings that this woman had to have been a druid. And once again, while I think that’d be awesome if it were the case, there’s just no strong evidence to suggest she wasn’t “merely” a powerful queen or warrior princess or some other important member of the Celtic aristocracy.

Then there’s the whole time issue. The Vix site dates back to 500 BCE, which is the Late Hallstatt / Early La Tène period. Which means technically I should have said Vix was a proto-Celtic site, but I digress. The Waldalgesheimer site dates to 330 BCE. A real spring chicken. It begs the question…

Were there even druids back then?

The short answer: probably.

The longer answer: Druids first appear in the historical record in the 4th century BCE. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t around before then. As British archaeologist Barry Cunliffe argues, the sophistication of ancient Celtic science and philosophy points to the existence of an intellectual elite. And I quote:

The rich fabric of prehistoric belief, revealed by the archaeological evidence especially in Britain, Ireland, and Armorica [modern Brittany], could only have been maintained by specialists – a group with coercive authority capable of abstract thought, philosophical speculation, and scientific observation, who passed on their learning from one generation to the next.

[…]

Could it be that the Druids, who are known to the Classical world from the 4th century BC, had their roots deep in this prehistory – that the accumulated wisdoms which they guarded and taught were the legacy of learning and practice going back into the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC? There is nothing at all unreasonable in this suggestion, indeed there is a logic in it, but there is no way in which it can be validated: it remains at best an interesting speculation.

source: Druids: A Very Short Introduction

“Interesting speculation” has pretty much been the modus operandi of this article from the start. (Or at least I hope it’s been interesting.) But now it’s time to put speculation aside (for like two seconds) while we look at some real, honest-to-goodness, no-bones-about-it (poor choice of words?) historical evidence for the existence of women druids.

The History of Female Druids

The first indisputable evidence for female druids appears in the historical record around 100 CE—the same year, incidentally, in which the aforementioned Plutarch described Celtic women serving as judges and battlefield negotiators in Mulierum virtutes (without labeling them “druids”). Fortunately, not all of Plutarch’s contemporaries were so reticent in regards to dropping the “D” word as a label for women.

An inscription discovered along the Rue de Récollets in Metz, France was dated to approximately 100 CE. What did that inscription say? Behold:

“Silvano sacr(um) et Nymphis loci Arete Druis antistita somnio monita d(edit)”

What? You don’t speak Latin?

Alright, here’s my v1, best-effort translation:

Sacred to Silvanus and to the Nymphs of the place of Arete the Druid, the high priestess who gave advice/warnings in a dream

Now, apparently “Druis” is in the genitive case according to the Epigraphic Database Heidelberg. That same resource says that Druis is also a patronymic. So perhaps it’s not “Arete the Druid”, but something like “Arete, daughter of the Druid”. Either way, the next word, antistita, clearly refers to a female “high priest” or “overseer.”

The bottom line: We’re looking at an inscription that reads almost like a public park dedication. Unless I’m interpreting this completely wrong (which is not out of the realm of possibility), the writer is dedicating this sacred place to the druidess Arete in honor of the god of the woods (Silvanus) and the local Nymphs. Although another interpretation I’ve seen says that the inscription was actually created by the druidess Arete as a way for her to honor Silvanus and the Nymphs. Regardless, the implication is the same:

There was a female druid in Gaul circa 100 CE. And we have a written record of her.

As an artifact, the inscription is certainly an intriguing one, especially when we remember that the ancient Gaulish Celts traditionally didn’t write anything down and, as far as I can tell, they didn’t have a written alphabet. (Ogham came later and was an Irish invention, although perhaps a proto version of the line-and-dash-based alphabet originated in Celtiberia/Spain.) So it actually makes sense that whoever wrote the Metz inscription wrote it in Latin and used Greco-Roman equivalents when referencing religion/mythology. Thus, the Celtic agricultural god Sucellos was referred to by the name of his Roman cognate, Silvanus.

Did the Metz inscription mark the first definitive appearance of female druids in the historical record? Depends who you ask. Some claim the historian Tacitus, who provided the first and only Roman account of druids in Britain, mentions druidesses in his Annals. Writing in 100 CE or so about events that took place in 60 or 61 CE, Tacitus noted the following:

On the beach stood the adverse array, a serried mass of arms and men, with women flitting between the ranks. In the style of Furies, in robes of deathly black and with dishevelled hair, they brandished their torches; while a circle of Druids, lifting their hands to heaven and showering imprecations, struck the troops with such an awe at the extraordinary spectacle that, as though their limbs were paralysed, they exposed their bodies to wounds without an attempt at movement. Then, reassured by their general, and inciting each other never to flinch before a band of females and fanatics, they charged behind the standards, cut down all who met them, and enveloped the enemy in his own flames.

source: Tacitus: Annals XIV

This was an account of Paulinus leading an assault on the Welsh island of Anglesey (or “Mona” to the Romans) before he became distracted by a revolution led by the one and only Boudicca. Back to the point: were the women “flitting between the ranks” dressed in “robes of deathly black and with dishevelled hair” actually druids? It’s entirely possible.

Jump ahead to Cassius Dio’s Roman History (211-233 CE) and we get another possible reference to a druidess—Ganna—who made an official visit to Rome.

Masyus, king of the Semnones, and Ganna, a virgin who was priestess in Germany, having succeeded Veleda, came to Domitian and after being honoured by him returned home.

Not much to go on there besides the word “priestess,” but it’s something.

Historia Augusta, likely written in the 4th century CE, is the first work (or collection of works, I should say) where female druids really shine. There are not one, not two, but three separate accounts in Historia Augusta of Roman emperors receiving prophecies from a Gaulish druidess, or “druiada“. First, there’s the Roman emperor Severus Alexander, who was assassinated as part of a conspiracy conceived by his own soldiers. The prophecy alludes to this fate very directly:

The omens portending his [Alexander’s] death were as follows: When he was praying for a blessing for his birthday the victim escaped, all covered with blood, and, as he was standing in the crowd dressed in the clothes of a consideration, it stained the white robe which he wore. In the Palace in a certain city from which he was setting out to the war, an ancient laurel-tree of huge size suddenly fell at full length. Also three fig-trees, which bear the kind of figs known as Alexandrian, fell suddenly before his tent-door, for they were close to the Emperor’s quarters. Furthermore, as he went to war a Druid prophetess cried out in the Gallic tongue, ‘Go, but do not hope for victory, and put no trust in your soldiers.‘ And when he mounted a tribunal in order to make a speech and say something of good omen, he began in this wise: ‘On the murder of the Emperor Elagabalus’. But it was regarded as a portent that when about to go to war he began an address to the troops with words of ill-omen.

source: Historia Augusta: The Life of Severus Alexander

Then there’s the Roman emperor Aurelian, who essentially asked some female druids to read his fortune (and the fortunes of his descendants). Here’s how it went down:

“[O]n a certain occasion Aurelian consulted the Druid priestesses in Gaul and inquired of them whether the imperial power would remain with his descendants, but they replied…that none would have a name more illustrious in the commonwealth than the descendants of Claudius. And, in fact, Constantius is now our emperor, a man of Claudius’ blood, whose descendants, I ween, will attain to that glory which the Druids foretold. And this I have put in the Life of Aurelian for the reason that this response was made to him when he inquired in person.”

source: Historia Augusta: Life of Aurelian

Finally, one of the (alleged) authors of Historia Augusta, Flavius Vopiscus, recalled a prophecy given to the (future) Roman emperor Diocletian by a Tungri druidess—the Tungri being a Celtic tribe in the Belgic region of Gaul. It appears Diocletian conferred with the druidess on a daily basis while stationed in Tungri.

This story my grandfather related to me, having heard it from Diocletian himself. “When Diocletian,” he said, “while still serving in a minor post, was stopping at a certain tavern in the land of the Tungri in Gaul, and was making up his daily reckoning with a woman, who was a Druidess, she said to him, ‘Diocletian, you are far too greedy and far too stingy,’ to which Diocletian replied, it is said, not in earnest, but only in jest, ‘I shall be generous enough when I become emperor.’ At this the Druidess said, so he related, ‘Do not jest, Diocletian, for you will become emperor when you have slain a Boar (Aper).'”

source: Historia Augusta: The Lives of Carus, Carinus and Numerian

Female Druids in Irish Mythology

To conclude, we shall leave behind the realm of history and dip our toes into mythology, for that is where we can find the most compelling references to female druids.

In the collection of early Irish poems and stories called the Dindsenchas (also: Dindshenchas, Dinnseanchas, Dinnsheanchas, or Dınnṡeanċas), which translates to “lore of places”, it is very clearly stated that female druids—ban-druí, “woman druid”—are part of the druidic order. The naming convention is similar to what we see for the banshee, bean-sidhe, meaning “woman fairy” or “woman of the fairy mound.”

Historian Peter Berresford Ellis gives the following example of women druids playing a key role in one of Irish mythology’s greatest battles:

Before the second battle of Magh Tuireadh, it is stated, two female druids promised to enchant the Fomorii army and cast a spell so that ‘the trees and stones and soda of the earth…shall become a host against them and rout them.’

source: A Dictionary of Irish Mythology

Ellis goes on to write that “[t]he role of female druids is also noted in later Christian ecclesiastical writings,” making it clear that Irish druidesses weren’t merely figments of folklore and mythology but living, breathing people who Christian missionaries encountered in Ireland.

Irish professor and folklorist Dáithí Ó hÓgáin goes so far as to suggest that Brigid of Kildare, the patroness saint of Ireland, was actually a chief druid who oversaw the temple of the goddess Brigid (hence the adoption of the name Brigid). Ó hÓgáin and others speculate that the druidess converted the temple into a Christian monastery sometime in the late 5th century, and thus the attributes of the Irish goddess Brigid and the druidess-turned-saint Brigid became intertwined. Their feast days now fall on the same day: Imbolc.

Further Reading

The World of the Druids by Miranda J. Green

War, Women, and Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts of the Ancient Celts by Philip Freeman

Myth, Legend, and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of Irish Folk Tradition by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

The Druid Animal Oracle by Philip and Stephanie Carr-Gomm

The Druid Plant Oracle: Working with the Magical Flora of the Druid Tradition by Philip and Stephanie Carr-Gomm

Midlife Dawn (Druid Heir Book 1) by N. Z. Nasser

The One and Only Crystal Druid (The Guild Codex: Unveiled Book 1)

by Annette Marie

Want to learn about the darker side of Irish mythology? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook The Path of Druidry: Walking the Ancient Green Way by Penny Billington (narrated by Jennifer M. Dixon). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 15-hour audiobook for free.

Loving the research and your writing style: informative yet witty!

LikeLiked by 2 people