Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

We all know the story.

Or actually, maybe not. Here, scooch in closer.

The year was 1999. A simpler time.

The country? Ireland.

The headline: “Fairy bush survives the motorway planners.”

Or as the Independent put it, a bit more cheekily: “Irish road side-tracked by the fairies’ right of way.”

Oor as it was phrased on my side of the pond: “If You Believe in Fairies, Don’t Bulldoze Their Lair.”

In short, the issue here was that plans for a new multi-lane road was going to require the removal of a bush near Latoon Creek in County Clare.

But this was no ordinary bush.

As high school teacher and seanchaí (traditional Irish storyteller) Eddie Lenihan explained at the time, a local farmer believed the Latoon bush marked the site of an infamous battle that took place between the fairies of Munster and the fairies of Connacht.

Thus, disturbing such a feature would be, at best, sacrilegious, and at worst, an invitation for retribution from the fairy world.

Because as you may have seen in my article/video on clurichauns, Irish fairies are not always the most peaceful or forgiving of supernatural beings.

Thankfully, Lenihan’s advocacy helped ensure the fairy bush’s preservation, and the motorway was diverted to go around it.

Now, in the aftermath of this fray between fay and infrastructure, the conversation in Ireland—and beyond—largely centered around belief in the supernatural.

Are fairies real? How many people actually believe in them? And why are the Irish so darn superstitious?

Taking a backseat to this conversation was, in my opinion, a much more interesting one, one that focused more on the natural than the supernatural:

Why, for centuries, have some trees (and bushes) been considered sacred in Irish culture?

And what can Irish mythology potentially teach us about this Irish reverence for trees?

Yes, to be sure, there is going to be some overlap with the fairy world.

But viewed through a purely historical lens, we can see that the idea of some Irish trees being sacred is likely connected to a broader, Celtic concept.

And because I know people love to argue about this, let me clarify that by “Celtic,” I mean speakers of Celtic languages.

In addition to the Gaels, who would settle in what is now Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, these include the Britons, who would settle in Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany, as well as the so-called Continental Celts, like the Boii, the Celtiberians, the Gallaeci, the Galatians, the Gauls, and the Lepontii.

And yes I know Brittany is part of Continental Europe, but technically the Bretons are lumped in with the Insular Celts, even though it makes more sense to divide Celtic-speakers into “P-Celtic” and “Q-Celtic” groups, based on the consonant sounds their respective languages favor. It’s a whole thing.

Back to the trees.

FYI: You can watch a video adaptation of this article right here:

The Sacred Groves of the Oak-Knowers (re: Druids)

According to the Greek geographer and historian Strabo, writing in the first century CE, the Galatians would assemble a council of three hundred men to pass judgment on murder cases. And their assembly place Strabo called the Drynemetum a.k.a. the Drunemeton, which translates to something like “oak sanctuary,” with nemeton meaning “sanctuary” or “sacred place,” and dry or dru meaning oak.

Indeed, some scholars have argued that the word druid relies on that same root, dru, and when combined with wid, meaning “to know,” gives us a literal translation of druid as “knower of the oak.”

This aligns quite nicely with what the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, also writing in the first century CE, had to say about the druids of Gaul:

“The Druids – for so their magicians are called – held nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and the tree that bears it, always supposing that tree to be the oak. But they choose groves of oaks for the sake of the tree alone, and they never perform any of their rites except in the presence of a branch of it.”

For yet another first-century take on a sacred druid grove, let us turn to the Roman poet Lucan and his description of a “nemeton” near what is now Marseille, France—a nemeton that Julius Caesar was said to have destroyed in the first century BCE.

However, a quick caveat is required before we dive in:

The description you’re about to hear is extremely propagandist. Or propagandistic, depending on your preferred adjective. Still, there is likely some sliver of truth in it, hence its inclusion here.

There was a grove, untouched through long centuries,

whose interlacing boughs enclosed cold and shadowy

depths, the sunlight banished far above. It was sacred

to no rural Pan, no Silvanus king of the wood, nor

to the Nymphs, but gods were worshipped there with

savage rites, the altars piled high with foul offerings,

and every tree drenched in human blood. On those

boughs, if ancient tales, respectful of deity, may be

believed, the birds feared to perch; in those coverts

no wild beast would lie; on that grove no wind ever

blew, no lightning bolt from the storm clouds fell;

and the trees, spreading their leaves to an absent

breeze, rustled of themselves. Water flowed there

in copious dark streams, while the images of the gods,

rough-hewn and grim, were merely crude blocks cut

from felled trunks of trees. But their very age itself,

and the ghastly colour of their rotting timber struck

terror; men feel less awe of deities in familiar forms;

their fear increases when the gods they dread appear

as alien shapes. They also say the subterranean caves

often shook and roared, that yew-trees fell and then

rose again, that flame glowed from trees free of fire,

while serpents slithered and twined about their trunks.

The people never gathered there to worship; they had

abandoned the place to the gods, and when the sun

was at the zenith, or night’s blackness seized the sky,

the priest himself dreaded those moments, afraid

of surprising the lord of the wood.

Yowza.

Staying within Continental Europe, I feel Brittany’s Paimpont Forest deserves a mention given that many scholars believe it was the inspiration for the Brocéliande Forest from Arthurian Legend.

The forest is home to the so-called Tomb of Merlin, a remnant of a dolmen. And while the site has become popular amongst neo-druids and neo-pagans, it’s important to note that the megalithic structures found within the forest date back to the Neolithic, as is the case with many of the megalithic structures discovered in what we think of as the Celtic world, meaning they actually predate the emergence of Celtic culture.

That’s not to say the Celts didn’t use these structures for their own ritual purposes and attach their own mythologies to them, they absolutely did, they just didn’t build them.

Moving on.

Sacred groves also appear to have been ubiquitous across Celtic Britain. Notably, another first-century Roman, the historian Tacitus, gave an account of the Roman conquest of the Welsh island of Anglesey, in which he noted:

“A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed. They deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails.”

And while no traces of this grove appear in the archaeological record—perhaps on account of the destroying, although it’s possible Tacitus just made it up, repeating what he’d heard from his predecessor Lucan—it’s worth noting that one of the largest collections of Early Celtic art, specifically metalwork done in the La Tène style, was discovered next to a lake on Anglesey.

And a few of these metal items, it turns out, were made in Ireland.

Yes, that’s the segue I’m using to take us back to the Emerald Isle, where the remnants of sacred Celtic groves can perhaps be found in popular place names.

Irish Places Named for Sacred Trees and Groves

For example, Derry was originally called Doire Calgaich, meaning “Calgach’s oak grove.”

Durrow in County Offaly was originally Darú, meaning “plain of the oaks.” And the abbey at Durrow, it should be noted, is one of the last remaining spots in Ireland where one can find pre-medieval oaks.

Toberbilly in Country Antrim, meanwhile, was originally Tober Bile, meaning “well of the ancient tree.”

Then there’s Kildare, which gets its name from the monastery founded by Saint Brigid, Cill Dara, meaning “church of the oak,” a monastery that may have originally been the site of a temple devoted to the Irish goddess Brigid. And according to Irish folklorist Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, the human Brigid may have been the chief druid of that temple prior to her conversion to Christianity.

Regardless, it is said that St. Brigid named the site after a beautiful oak tree that she “loved much,” and “under whose shade she built her first little oratory.” This according to the Irish clergyman John Healy, who went on to note that the “tree remained down to the end of the tenth century…and it was held in such veneration that no profane hand dare venture to touch it with a weapon.”

Sacred Trees in Irish History

Brigid’s veneration of the oak aligns perfectly with what we find in the 8th-century Irish law-text Bretha Comaithchesa, “judgements of neighbourhood,” in which Ireland’s native trees are divided into classes and corresponding penalties are designated based on injuries inflicted upon said trees.

There are seven “Class A” trees or “Lords of the Wood,” according to the text, which are as follows:

- 1. Oak

- 2. Hazel

- 3. Holly

- 4. Yew

- 5. Ash

- 6. Scots pine

- 7. Wild apple-tree

Now, a mere branch-cutting of one of these Lords of the Wood would set you back a year-old heifer. A fork-cutting would set you back a two-year-old heifer. But a base-cutting? Hoo boy. That’d cost you a milk cow.

But apparently these injury-specific fines were paid on top of an initial fine equivalent to two milk cows and a three-year-old heifer.

All this to say: the Irish took their trees seriously.

In his Dictionary of Irish Mythology, historian Peter Berresford Ellis noted that “[e]ach clan or confederation of clans had its sacred tree or bile. Not infrequently reference is made to a hostile clan invading a territory and felling a sacred tree as a dramatic gesture which would shame and demoralise their enemies for many of these trees were considered as the crann bethadh, ‘tree of life’.”

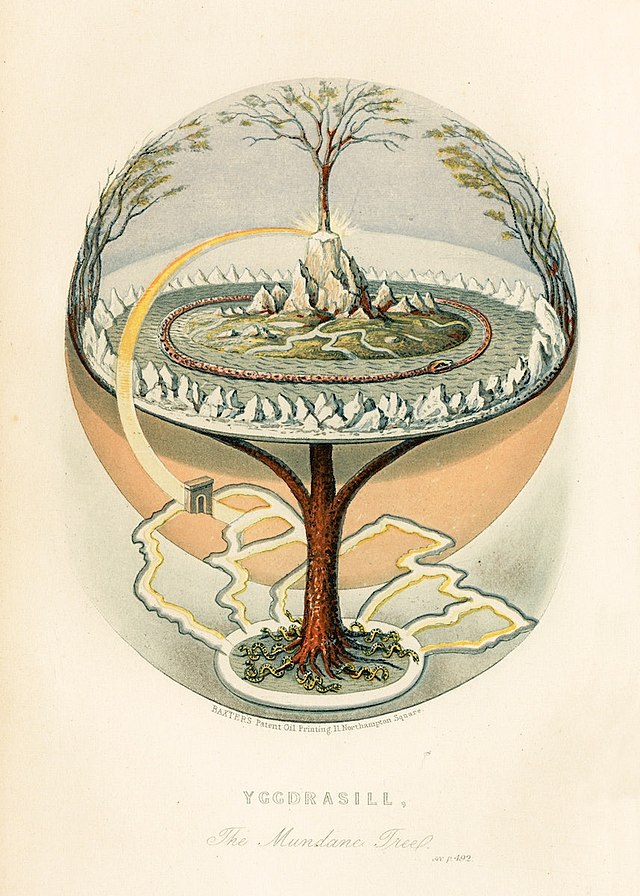

From a comparative mythology perspective, the tree of life can be thought of as a Celtic iteration of the world tree or axis mundi, a concept I explore in more detail in my article/video Beltane Explained: May Day’s Celtic Origins.

But keeping our perspective rooted in history, or quasi-history at least, these sacred trees, known in Irish as bile (meaning “ancient tree”), or defhid (meaning “god tree”), or fidnemed (a term that may have a linguistic connection to the aforementioned nemeton), were typically situated near the centers of a given territory and were considered sources of pride amongst local inhabitants.

What’s more, to Ellis’ point, the very significance of these trees made them vulnerable to attack.

According to the Annals of Ulster, the Cenél nEógain (Kinel-Owen), a branch of the Northern Uí Néill dynasty, defeated the the Ulaid (i.e., Ulstermen) in a battle in 1099 C.E., and, to add insult to injury, they cut down the Ulaid’s sacred tree, the Craeb Telcha.

Fast forward to 1111 and the Ulaid would have their revenge, when, “[a]n expedition was made by the Ulaid to Telach Óc [the royal seat of the Cenél nEógain], and they cut down its sacred trees.”

On occasion, nature itself was the enemy, so to speak, as the Annals of Ulster also record that in 996, “[l]ightning struck Ard Macha [modern: Armagh] and it did not leave unburnt an oratory, stone church, vestibule or wooden sanctuary.”

The Irish word translated as “wooden sanctuary” here is actually one we learned earlier: fidnemed. This according to Irish woodland expert Fergus Kelly, who, in a lecture given to the Society of Irish Foresters, also noted the following:

“It is probable that some of these specially venerated trees continue a tradition of tree worship going back to pre-Christian times.”

And that leads us to the Dindshenchas, or “Lore of Places,” a collection of poems, tales, and commentaries which, while transcribed in Christian times, are undoubtedly pre-Christian in origin.

The Five Sacred Trees of Ireland

In two of the 176 poems recorded in the Dindshenchas, poems number 23 and 24 to be precise, we learn about five trees that were, apparently, very important to the ancient Irish. And I quote:

Eo Mugna, great was the fair tree,

high its top above the rest;

thirty cubits — it was no trifle —

that was the measure of its girth.

Three hundred cubits was the height of the blameless tree,

its shadow stretched a thousand cubits:

in secrecy it remained in the north and east

till the time of Conn of the Hundred Fights.

A hundred score of warriors — no empty tale —

along with ten hundred and forty

would that tree shelter — it was a fierce struggle —

till it was overthrown by the poets.

That was the first tree, the Eo Mugna or Oak of Mugna, as described in poem 23. And as you’re about to hear, this oak gets another mention in poem 24, in which the rest of trees are also listed:

How fell the Bough of Da Thí?

it sheltered the strength of many a gentle hireling:

an ash, the tree of the nimble hosts,

its top bore no lasting yield.

The Ash in Tortu — take count thereof!

the Ash of populous Usnech.

their boughs fell — it was not amiss —

in the time of the sons of AEd Slane.

The Oak of Mugna, it was a joyous treasure;

nine hundred bushels was its bountiful yield:

the beautiful oak tree fell,

across Mag Ailbe of the cruel combats.

The Bole of Ross, a comely yew

with abundance of broad timber,

the tree without hollow or flaw,

the stately bole, how did it fall?

Today, these five trees—the Eo Mugna (an oak), the Bile Dathi (an ash), the Bile Tortan (an ash), the Craeb Uisnig (another ash), and the Eo Rossa (a yew)—are collectively known as the five sacred trees of Ireland.

They are so sacred, in fact, that John Williams—yes, that John Williams—composed a piece of music about them, appropriately titled The Five Sacred Trees, with each tree receiving its own movement.

Williams drew inspiration for the piece from the works of British novelist and poet Robert Graves, son of the Irish poet Alfred Perceval Graves, and, for the sake of thoroughness, I’m going to include Williams’ liner notes in which he described the significance of each of the sacred trees.

However, please keep in mind that not all of what you’re about to hear is actually attested to in the myths, as Robert Graves notoriously took a lot of liberties when writing about Irish mythology.

Alright, here we go. The first movement:

“Eó Mugna, the great oak, whose roots extend to Connia’s Well in the “otherworld,” stands guard over what is the source of the River Shannon and the font of all wisdom. The well is probably the source of all music, too. The inspiration for this movement is the Irish Uillean pipe, a distant ancestor of the bassoon, whose music evokes the spirit of Mugna and the sacred well.”

Second movement:

“Tortan is a tree that has been associated with witches and as a result, the fiddle appears, sawing away, as it is conjoined with the music of the bassoon. The Irish Bodhrán drum assists.”

Third movement:

“The Tree of Ross (or Eó Rosa) is a yew, and although the yew is often referred to as a symbol of death and destruction, The Tree of Ross is often the subject of much rhapsodizing in the literature. It is referred to as “a mother’s good,” [and] “Diadem of the Angels,”…Hence the lyrical character of this movement, wherein the bassoon oncants and is accompanied by the harp!”

Fourth movement:

“Craeb Uisnig is an ash and has been described by Robert Graves as a source of strife. Thus, a ghostly battle, where all that is heard as the phantoms struggle, is the snapping of twigs on the forest floor.”

Fifth movement:

“Dathi, which purportedly exercised authority over the Poets, and was the last tree to fall, is the subject for the close of the piece. The bassoon soliloquizes as it ponders the secrets of the Trees.”

Of course, Irish trees didn’t only inspire modern composers of classical music, they also seemingly inspired ancient composers of alphabets. Or at least one alphabet, anyway, Ogham, which is also known as the Celtic tree alphabet on account of its letters being named after different varieties of trees.

The Ogham/Sacred Tree Connection

For example, according to a medieval list called the Bríatharogam (or “word ogham”), A is ailim (“elm”); B is beithe (“birch”); C is coll (“hazel”); and so on.

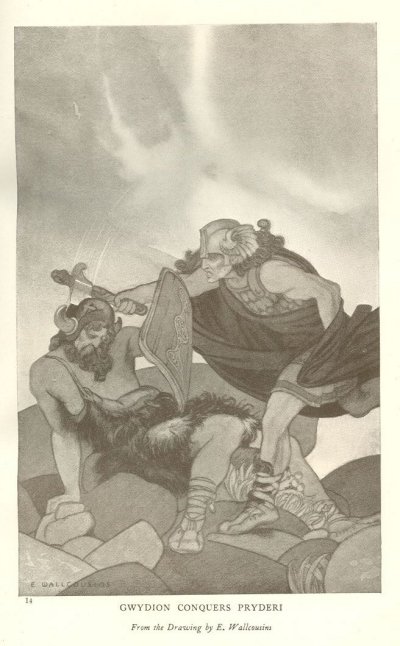

And this leads us back to Wales, to a poem recorded in the 14th-century Book of Taliesin called “Cad Goddeu” or “The Battle of the Trees,” in which the magician Gwydion enchants the trees of a forest, animating them and enlisting them to fight as his army. (Ent that a familiar tale?)

Our old pal Robert Graves speculated that the pugilistic trees listed in the poem correspond to the letters of the Ogham alphabet, and that the whole thing was essentially a veiled reference to druidic or druidical (pick your adjective) secrets.

And while this interpretation is not widely accepted, what is widely accepted is that Gwydion is by no means the only magic-wielding character from a Celtic storytelling tradition to enlist the help of trees in battle.

Sacred Trees in Irish Mythology

In the lead up to the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, from the redundantly named Mythological Cycle of Irish Mythology, the god of many talents Lugh asks his enchantresses Bé Chuille and Dianann how they will aid the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Irish gods, in their fight against Balor of the Evil Eye and the Fomorians. Their response:

“We will enchant the trees and the stones and the sods of the earth so that they will be a host under arms against them; and they will scatter in flight terrified and trembling.”

FYI: You can learn more about the bewitching character Bé Chuille in my article/video on the most powerful druids from Irish mythology.

For the most part, however, characters in the Irish myths don’t seek out trees for purposes of violence, but for refuge from violence.

And in no story is this better encapsulated than Buile Shuibhne, the Madness of Sweeney, in which the titular Sweeney, king of the Irish territory of Dal Araidhe, flees the battle of Magh Rath in a frenzy after being cursed by a saint.

Suibne Geilt, or Mad Sweeney, as he comes to be called, seeks refuge in the woods and for years lives a bird-like existence perched in the branches of trees. Indeed, he is resting on the “summit of a tall ivy-branch,” when he delivers the following eulogy of the trees of Ireland:

Thou oak, bushy, leafy,

thou art high beyond trees;

O hazlet, little branching one,

O fragrance of hazel-nuts.

O alder, thou art not hostile,

delightful is thy hue,

thou art not rending and prickling

in the gap wherein thou art.

O little blackthorn, little thorny one;

O little black sloe-tree;

O watercress, little green-topped one,

from the brink of the ouse spring.

O minen of the pathway,

thou art sweet beyond herbs,

O little green one, very green one,

O herb on which grows the strawberry.

O apple-tree, little apple-tree,

much art thou shaken;

O quicken, little berried one,

delightful is thy bloom.

O briar, little arched one,

thou grantest no fair terms,

thou ceasest not to tear me,

till thou hast thy fill of blood.

O yew-tree, little yew-tree,

in churchyards thou art conspicuous;

o ivy, little ivy,

thou art familiar in the dusky wood.

O holly, little sheltering one,

thou door against the wind;

o ash-tree, thou baleful one,

hand-weapon of a warrior.

O birch, smooth and blessed,

thou melodious, proud one,

delightful each entwining branch

in the top of thy crown.

The aspen a-trembling;

by turns I hear

its leaves a-racing—

meseems ’tis the foray!

My aversion in woods—

I conceal it not from anyone—

is the leafy stirk of an oak

swaying evermore.

Quite a contrast from the way the Roman poet Lucan described a Gaulish forest, isn’t it?

In Irish mythology, forests and the trees that comprise them are not gloomy harbingers of doom, but symbols of peace and enlightenment.

Apple branches and the fruits they bear are the passports that grant Irish heroes access to the Land of Youth, and the Land of Promise, and other wondrous Otherworlds.

Nine hazel trees mark the mythical source of the Boyne river, the Well of Segais (Segais meaning “forest”), and from these trees fall the Nuts of Inspiration, which are consumed by a fish, the Salmon of Knowledge, imbuing it with infinite wisdom, and, by extension, imbuing the salmon-consuming hero Fionn mac Cumhaill with this wisdom as well.

And to bring all of this sacred tree lore back to the superstitiousness of the Irish, ever wonder why people knock on wood in order to ward off bad luck?

It’s been theorized that this timber-based jinx-blocking strategy arose in the groves of the ancient Celts, who would knock on tree trunks either to summon the protection of the spirits within, or to thank the trees for providing a bushy, leafy sanctuary.

Want to learn about the darker side of Irish and Celtic mythology? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Irish Monsters in Your Pocket

In the Ireland of myth and legend, “spooky season” is every season. Spirits roam the countryside, hovering above the bogs. Werewolves lope through forests under full moons. Dragons lurk beneath the waves. Granted, there’s no denying that Samhain (Halloween’s Celtic predecessor) tends to bring out some of the island’s biggest, baddest monsters. Prepare yourself for (educational) encounters with Irish cryptids, demons, ghouls, goblins, and other supernatural beings. Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes by Philip Freeman (narrated by Gerard Doyle). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 7.5-hour audiobook for free.